Prolonged calorie restriction seen in many fad diets is not a sustainable practice. Weight will be lost for sure, but a significant amount of the disappearing pounds will be from valuable muscle mass. Loss of muscle mass with prolonged caloric restriction has a huge health cost in the long term, especially for those with metabolic diseases such as diabetes and the aging population. Adequate muscle mass is vital to maintain metabolic health and prevent frailty as we age. It is also impossible to work out at high enough intensities to achieve the beneficial adaptive responses to exercise while undergoing long term calorie restricted diets. Our engines need adequate fuel to perform optimally.

Prolonged caloric restriction has been shown to extend the life span of rodents, worms, and fruit flies, but longer life spans have not been seen from fasting in higher primates and humans. What is clear is that periodic fasting has been shown to improve the health span in humans and can be highly effective in reversing chronic diseases if done properly.

The issues with prolonged calorically restricted diets for weight loss and the proven benefits with periodic fasting have led many of us to experiment with intermittent fasting (IF). Intermittent fasting is the practice of scheduling short term periods of calorie restriction, followed by normal caloric intake. Recent science has shown that many of the metabolic benefits of fasting can be achieved with IF without the loss of our prized muscle mass. For this reason, IF has gained popularity in recent years. For some IF works fantastically to achieve a lean physique and metabolic health, while others have not been so successful with their experiments with short scheduled fasting. What gives? Why do some people see great results with IF and others crash and burn? Much of the variability with results likely is from the “environmental” context IF is used. Let’s go back to first principles to establish a framework for successfully using intermittent fasting.

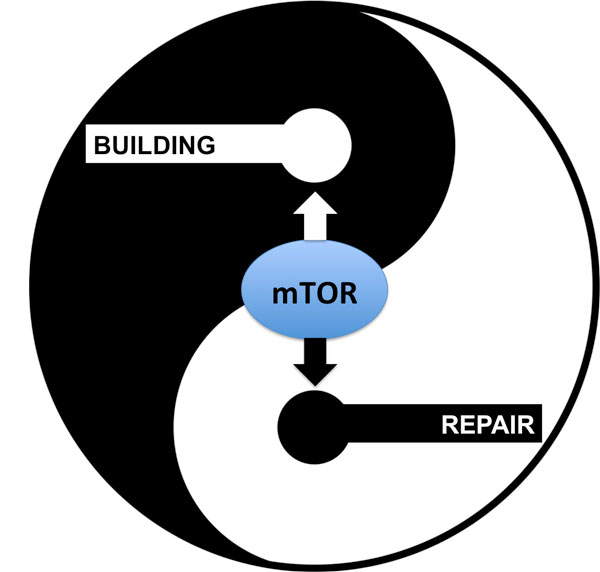

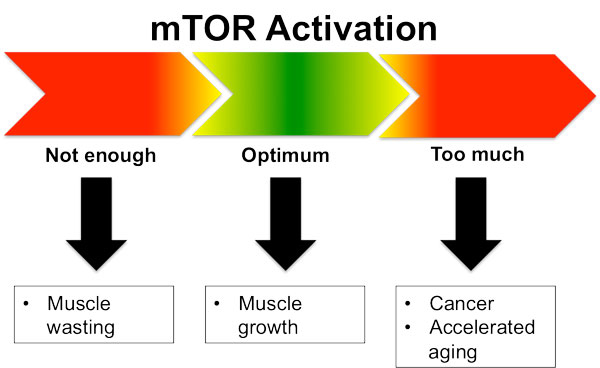

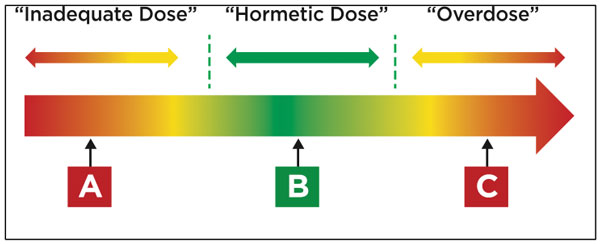

Intermittent fasting is an environmental stress (remember that our environment includes all aspects of our lifestyle) on the body and brain. The short-term stress of IF activates the repair and recycling system of autophagy we covered in Part I. Intermittent fasting will temporarily shut off the mTOR building pathway in favor of repair. The autophagy system improves the health and metabolic efficiency of our cells which translates into beneficial effects for our entire body. “Dosed” correctly, IF can be the missing link in your quest for optimum health, body composition, and prevention of chronic disease. The important point to remember is that although potentially beneficial, intermittent fasting like all caloric restriction contributes to your daily “stress cup” (aka allostatic load discussed in Strong Medicine).

The proper dose of IF is a moving target, as the other contributors to your daily stress cup determines how much caloric restrictions you can handle (if any) on any given day. If you have had a night of bad sleep and significant work or social stress, there will be very little room for the added stress of intermittent fasting. If you don’t take into account a nearly full stress cup and press ahead anyway with a significant fasting period that day, your stress cup will overflow (allostatic overload). This will create a substantial response from the HPA axis (stress system) and increase your cortisol levels. Your brain is protecting itself utilizing increased HPA axis activation and resulting high cortisol levels during allostatic overload situations. This response ensures the brain has adequate glucose, even if it has to get it from your precious muscle mass (from amino acids using gluconeogenesis- see Strong Medicine for more).

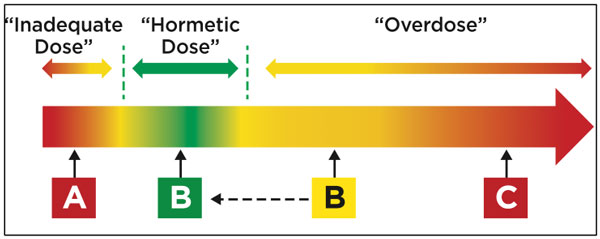

We can frame the “dosing” of IF using the concept of hormesis. From Strong Medicine, we know that hormesis is the phenomenon of something that is potentially bad for us can be beneficial at the proper dose. Calorie restriction certainly follows the concept of hormesis- small amounts produce a beneficial response while large amounts lead to a starvation state. A crucial concept to understand is that the same dose of fasting can be beneficial one day detrimental the next day depending on the state of your stress cup. This is how hormesis and allostasis are intertwined.

The benefits of IF-induced autophagy will not be realized if you overdose your fasting period. This point deserves repeating- intermittent fasting is a stress on your body and has to be balanced with the other stresses in your life to do it successfully.

Exercise and Intermittent Fasting

Finding the right mix of high intensity exercise and fasting can be a very tough to consistently pull off. High intensity resistance training and interval training stimulates the mTOR building pathway, increasing/maintaining our muscle mass and promoting fat loss through the actions of growth hormone. High intensity exercise is also a significant stress (which is why it works) on the body and needs to be figured into your daily stress cup evaluation. This type of training directly after a period of fasting can be especially stressful and should be approached with caution and careful assessment of your stress cup.

General guidelines

For the lucky few that live idyllic lives (my Strong Medicine co-author, Marty Gallagher, comes to mind) and have relatively empty stress cups, you can get away reckless forays into fasting experimentation and be just fine. Most of us are not that lucky and need a few guidelines to keep us out of trouble:

- Assess your stress cup daily. Fasting is never a good idea with an already-full stress cup.

- Start with brief fasting periods when beginning IF. The most popular is fasting from dinner the night before until lunch time the following day.

- Avoid fasting when planning high intensity exercise sessions that day (“feed your activity” concept from Strong Medicine). Fueling your post-workout time periods will help maximize mTOR and muscle building. If you are getting good results starting your work out in a fasted state, make sure you feed yourself adequately post-workout.

- Avoid fasting after a night of poor sleep. Poor sleep is one of the biggest contributors to the stress cup.

- Plan fasting on your non-exercise recovery days. This can help maximize effectiveness of the repair/recycling autophagy system.

- If you can’t handle complete fasting try a reduced protein day. Recall that amino acids from protein are potent triggers of the mTOR building system and reduced protein intake will trigger autophagy without abstaining completely from food. Meals consisting of high fiber vegetables with additional fats from olive oil/coconut oil or avocados will work well for this reduced protein strategy.

- For those of us pushing middle age it is important that we give potent stimulation of the mTOR pathway to slow the muscle wasting of aging (sarcopenia). It is harder for the aging trainee to stimulate mTOR compared to the younger person. If this applies to you, consider a weekly schedule with less overall fasting and more attention to resistance training with increased protein intake to find your optimal balance between building and repair.

Conclusion

Intermittent fasting practice that is informed by daily monitoring of your stress cup can be hugely beneficial. The key is to be flexible and not overly rigid with planning your fasting. If you are having a high stress cup day, don’t be afraid to ditch your fasting plans. Failing to take allostatic load (stress cup) into account will just hurt you in the long run and slow progress to attaining your fitness and health goals. Start slowly with short fasting periods and increase with small increments. Using the conceptual framework we have created with intermittent fasting and the stress cup you can find your optimal individual balance between building and repair.

****

Chris Hardy, D.O., M.P.H., CSCS, is the author of Strong Medicine: How to Conquer Chronic Disease and Achieve Your Full Genetic Potential. He is a public-health physician, personal trainer, mountain biker, rock climber and guitarist. His passion is communicating science-based lifestyle information and recommendations in an easy-to-understand manner to empower the public in the fight against preventable chronic disease.