This is the fifth and final post in a series of articles developed from Dr. Chris Hardy’s live presentation at Dragon Door’s Inaugural Health and Strength Conference. Click here to read the first article of the series. These questions were from the coaches, trainers, and fitness instructors in attendance.

Q: How do I measure HRV (heart rate variability) if I have eight people coming in for a group fitness class?

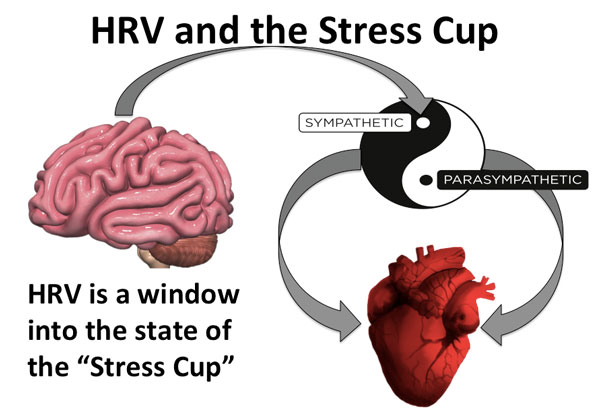

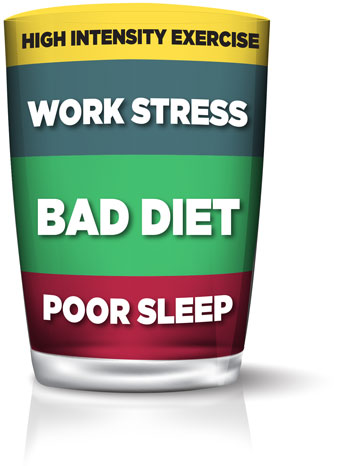

A: You would set this up with your clients beforehand. They would measure it first thing in the morning. In the back of Strong Medicine, I discuss how the optimum time to measure HRV is at first waking, before anything has an opportunity to fill the stress cup. This measurement will give them a baseline. Most HRV apps require two and a half minutes to measure and will use data from a chest strap like a Polar Bluetooth heart rate monitor. The app will determine the HRV as a number. It’s important to measure it first thing in the morning, because if you measure it throughout the day, even someone angering you in traffic will change it.

Measuring HRV is not perfect, but if you measure it the same time every day before anything else has effected your stress cup then it will be a good reference. It will also reflect if you’ve been up all night tossing and turning.

Q: I have a client who has a lap-band, so she’s only eating 200 calories a day. If she eats more she vomits yet she wants intense exercise. She’s stressed and thin but with a huge belly. How would we work with her if we can’t get her to eat more? Do we just take down the intensity?

A: First, it sounds like she’s protein deficient. And you won’t be able to workout with her—you can’t—it will hurt her. It’s like when people come to me and want antibiotics for a viral infection. Then, when I don’t prescribe the antibiotics, they just go to someone else who will. But you should not be training that person, because she could go off the rails in a second.

She’s protein deficient and malnourished. That large belly is basically a bunch of fluid because there’s so little protein in her bloodstream that an osmosis effect happens and draws water from the bloodstream, then it goes into the tissues. It’s called ascites, and patients will sometimes develop huge protuberant bellies. We see it happen in sub-Saharan Africa, and other places where people are malnourished. You need to say no, and she needs medical attention.

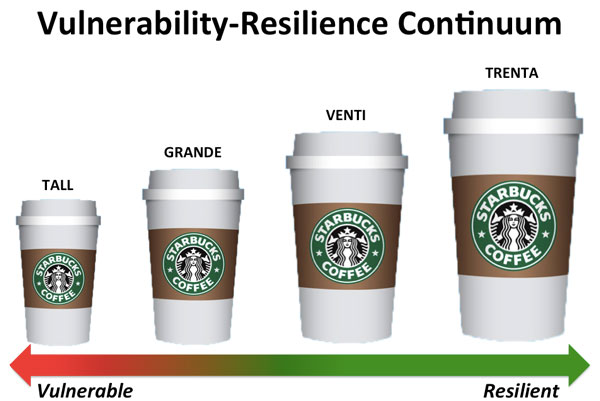

Q: We lead boot camps and have workouts on the board, what do you think about having our clients do their self reported health scale on the 1-5 range (will link to article) then adjust the workout accordingly?

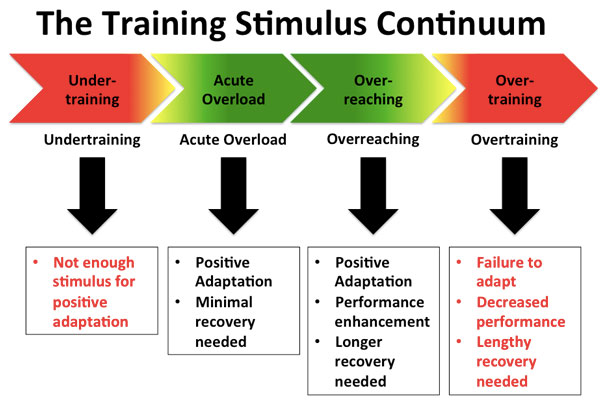

A: Or they can monitor their own heart rates. This is also where you can use your creativity and find your own opportunities. You can stratify the workouts. Educate them to let them know that if they’re lower on their rating scale to be smart and that “this isn’t a punishment”. They need to know to be smart because they won’t do themselves any good by crushing themselves on that day—they’re just end up with a lot of cortisol. You’ve seen the ultra-skinny marathon runners that still have a little bit of a belly? It’s because of a cortisol response.

Q: You said that you have your clients measure their heart rates in the morning. My training classes usually take place at 8PM after they come from work and have done finished their day. How will the HRV measurement from the morning reflect how they are when they walk into my gym at 8PM?

A: It’s true that it isn’t perfect, and that’s the problem. But, as long as they’re not doing intense physical training before they get to you, if they measure their HRV in the morning, the biggest thing they will be affected by is sleep. Since HRV is the variability of the heart rate as measured on an app, it gives you an idea of where you were that morning. If your HRV is already low that morning, it will just get worse throughout the day. So, if they come in with a low HRV recorded in the morning, by the time they see you—especially if they have had other stresses during the day—then their HRV will be even lower.

The morning measurement will give you a baseline, but that’s why you’ll also want to use the self-reporting scale. There’s too much that can happen during the day, and you’re trying to work with a consistent baseline. So, let’s say I usually run an “80” I’m picking an arbitrary number for my HRV, but that’s pretty high. But, this morning I measured my HRV and it was 62. When I come to train with you later that night I’ll tell you that my HRV was 62 this morning. Since I usually run in the 80s you would drop my workout down some. So in other words we are discounting what happened through the day unless a client did some other kind of training. It’s not a perfect system.

Q: What your favorite strategies for sleep? How do you feel about the different amounts of melatonin in supplements?

A: Sleep might be the same thing as attacking the circadian rhythm first. I hate to keep referring back to the book, but I do have a whole chapter on how to give your brain the right signals. So 2-3 hours before bedtime, no blue light from broad-spectrum sources. You can either use the goggles or my wife and I put yellow lights in the rooms where we spend our evening hours. We also follow basic sleep hygiene ideas—no electronics in the room. In the mornings we make sure to get bright, broad-spectrum light exposure, since most of us go to an office with poor lighting.

As for supplements, I am not a huge fan of melatonin, though I think it is very valuable for getting yourself back into another rhythm in the case of jet lag. The problem is most of the doses are supra-physiological. The pineal gland in the brain actually secretes melatonin on a pulse, about every 40 minutes since it has a very short half-life. Your body metabolizes melatonin supplements quickly, so it may help you fall asleep, but then you’re going to be back up again if you haven’t fixed your circadian rhythm. And it may also suppress your endogenous (internal) melatonin secretion.

Q: On Saturday and Sunday, 25-30 people come in to our gym for group classes. Either myself or the other trainer will greet the people as they are coming in and ask them how they are doing and how they are feeling. If they come in and say that they slept badly, just came home from an intense two-day conference, or they are still sore from working out, then we will then tell them that we will scale the workout of the day. We put up the workout and a scaled version in terms of volume or intensity and say that if we spoke to you and said you should do the scaled version, we can now train 20-30 people together.

A: I love it, but would say from a psychological point of view I would have them self-label.

Q: That was my follow up question. This is a physical/psychological assessment based on how they feel about today themselves that day, etc.

A: If a client comes in and says that they are feeling kind of cruddy, and then you say, “well we are going to do this to you” that takes some of the control from them. Instead you could have them self-label and say “I’m a 3 right now”. Since they put themselves in that category, it will be easier for them to understand that it’s not a punishment. They will just be doing the #3 workout today. It’s part of the psychology of getting them to buy in more because they have self-labeled.

Q: My question is goes back to using heart rate. How would you use the heart rate protocol with someone on beta-blockers?

A: That can be very inconvenient! Beta-blockers basically stick a wrench in the system, and prevent the heart rate from going up. It depends on why the client is on a beta-blocker—and if it is for arrhythmia then you don’t want to mess with it. But if someone is on a beta-blocker because their doctor is trying to use it as an inappropriate way to control high blood pressure, then you might suggest that they ask their doctor about alternatives. When someone is on beta-blockers, they will not be able to get their heart rate up, so rate of perceived exertion may be a better indicator for them.

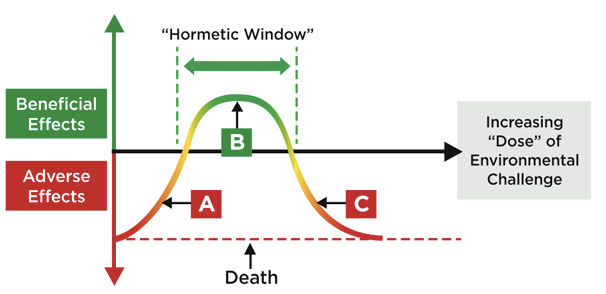

Q: Melatonin was already discussed as a supplement for sleep, but how would you say performance supplements like pre-workout or protein supplements would affect allostatic load?

A: That’s a great question and, they do affect the allostatic load. It goes back to the idea of feeding your activity. We need the proper amount of protein so that amino acids hit our anabolic pathways—mTOR, the anabolic pathway where certain branched chain amino acids will hit. It can give the body fuel for activity. You need to fuel your body and give it the precursors of what it needs—whole regular food is always the best, but that is not always possible. So, supplementing something like whey protein, or a post-workout combination of protein and some glucose sources can work well, but be sure to tailor it to your activity. Do you really need to load up with a huge serving of starch or glucose for strength training? Probably not. You’ll want to use amino acids instead.

Q: But in regards to pre-workout energy supplements, I’ve tried some that just made me feel extremely crazy and full of false energy…

A: Honestly, if you are going to do one, the supplement I think is best for pre-workout is creatine. It hits the phosphogen energy pathway. But I am not a fan of the supplements that “jack up the nervous system” they can work for younger people, but in the older population it can affect the stress cup.

Q: What are your recommendations for determining optimal heart rates for training and interval training? Do you have any recommendations for estimating or determining maximum heart rate? What if someone is on a beta-blocker? Is a VO2Max test, a stress test, or a simple calculation the best?

A: It depends on your client. If you are working with an elite athlete, then you should probably do one of the more clinical assessments. This is because we all know that the samples for calculating max heart rate are estimates and they’re for a general population. They aren’t necessarily appropriate for everyone because they can be underestimated. If you used the formula on an athletic 50-year-old, it may underestimate their max heart rate. Some of the formulas are better than others—certainly better than 220 minus age.

Q: When working with individuals who are nurses, police officers, fire fighters, and other shift workers, how do you help them make improve the sleep they are getting?

A: Shift work is actually classified as a carcinogen by large governing agencies. But they have done studies with shift workers and found that their environmental clues are the most important. Your circadian system is free running—they’ve done studies in caves in isolation—and will advance itself without external cues. Another study with police officers and nurses exposed them to maximum bright lights during their shifts at night—which was their mornings. Even though they are coming to their shift at night, they should get maximum bright light exposure. When they are coming home, they should use amber glasses or something to block out blue spectrum light. When they sleep, blackout curtains can make their environment as dark as possible. Are they getting perfect sleep? No, but these environmental cues can make a big improvement.

***

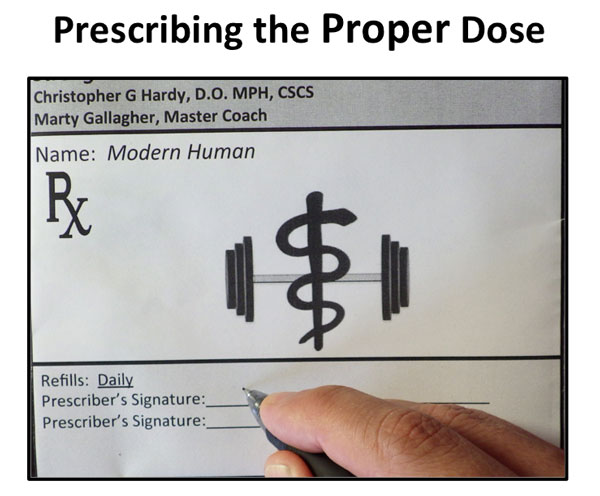

Chris Hardy, D.O., M.P.H., CSCS, is the author of Strong Medicine: How to Conquer Chronic Disease and Achieve Your Full Genetic Potential. He is a public-health physician, personal trainer, mountain biker, rock climber and guitarist. His passion is communicating science-based lifestyle information and recommendations in an easy-to-understand manner to empower the public in the fight against preventable chronic disease.

Dr. Hardy mentioned grip strength as a possible tool to measure the stress cup on a daily basis. There are studies that have shown that a decrease in grip strength is correlated with strokes, heart attacks and overall longevity—it made sense that it would also be an indicator of Central Nervous System health. I also liked the fact that it was a quick and easy check that I could do daily before I trained.

Dr. Hardy mentioned grip strength as a possible tool to measure the stress cup on a daily basis. There are studies that have shown that a decrease in grip strength is correlated with strokes, heart attacks and overall longevity—it made sense that it would also be an indicator of Central Nervous System health. I also liked the fact that it was a quick and easy check that I could do daily before I trained.

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) is broken into four primary practices: Qigong (where my expertise resides); herbal medicine; acupuncture; and massage. Due to some feathers I have ruffled, I will qualify all of my medical knowledge to be isolated to the Qigong perspective only. I have done the herbs and the medical massage, and since I am not licensed to needle anyone, I have no experience with acupuncture from the provider’s vantage point. Lucky for you, the Qigong is not only the most interesting of the four, but also considered to be the mother of the other three, philosophically.

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) is broken into four primary practices: Qigong (where my expertise resides); herbal medicine; acupuncture; and massage. Due to some feathers I have ruffled, I will qualify all of my medical knowledge to be isolated to the Qigong perspective only. I have done the herbs and the medical massage, and since I am not licensed to needle anyone, I have no experience with acupuncture from the provider’s vantage point. Lucky for you, the Qigong is not only the most interesting of the four, but also considered to be the mother of the other three, philosophically.

Chris Holder comes to the

Chris Holder comes to the