As my old powerlifting coach used to say about squatting, “If it’s excruciating, you’re likely doing it right.” He was addressing the idea that there is a fair amount of discomfort involved with proper squatting. Note I didn’t say “pain.” The word pain is so loosely used in fitness and it has lost its meaning. When the meatheads say, “No pain, no gain!” What they really mean to say is “there should be a certain amount of physiological discomfort accompanying most any effective progressive resistance exercise. When we exert maximally, as we should, there is discomfort, and it can be intensely “uncomfortable.” But our factual explanation doesn’t sound near as taunt or sexy as No Pain! No Gain!

Pain is accidentally slamming your hand in a car door or cutting yourself while dicing onions: grinding out the 5th rep of a result-producing hypertrophy-inducing set of goblet squats is extreme discomfort – not pain. We learn how to exert maximally without need to self-inflict a hernia or a stroke from strain. We need learn how to exert maximally, yet exert safely. There are three rules to remember when it comes to exerting with maximum effort in any hardcore progressive resistance training exercise….

- Push or pull evenly and always stay within the precise technical boundaries: most weight training injuries occur when the lifter strays outside the proscribed techniques for the specific exercise. We have archetypical techniques for all the major and minor exercises. Adhere as closely as possible to these technical ideals. The lifts are archetypical because the leverage is optimal and the push/pull position stable.

- Never twist, heave, contort or jerk on a weight: real iron pros use a smooth application of power to attain 100% (or more) of capacity. Push or pull maximally while braced internally; tight and muscled, exert with great deliberation and evenness. Those that break form, usually to slip or slide through a sticking point, get injured. Nothing gets you hurt quicker that jerking or contorting or trying to be cute with maximum poundage.

- Learn how to miss a rep safely: those that lift long enough and lift heavy enough will sooner or later miss a repetition. No big deal on a standing curl using a 60-pound barbell; it can be a very big deal if you miss the 5th rep in the back squat ¾ of the way up with 315 draped across your neck. There are real safety issues: hardcore resistance training can be injurious.

Stance: the first step in learning how to squat is “playing with” the squat stance width. The goal is to find a width that allows the squatter (you) to descend and ascend while adhering to our technical ideal: we seek to squat with vertical shins and a vertical torso, ideally only the femurs move as we rise and fall; moving with great deliberation and precision over an exaggerated range-of-motion. Every one has an ideal stance width that allows us to attain and maintain this signature squat stance width technique.

More than likely, when you find the correct stance width, one that allows you to sit upright in a bottommost squat position, when you go to arise, you will be weak as a kitten, likely unable to arise from the ultra-deep relaxed squat position without breaking form or without some sort of assistance. We do nothing in the course of living our normal lives that gives us power and strength in this extremely disadvantaged position.

However, by identifying the archetype, by finding that stance width particular to you and your particular bodily proportion, you are now ready for the next step: strengthening our legs by concentrating all our effort at getting stronger in this one very specific exercise, done a very specific way. Maximal squat difficulty results in maximum squat benefit: that which does not kill me makes me stronger – and gives me powerhouse, tree-trunk legs. So we squat using this weak-as-a-kitten stance and we hammer away and improve, one excruciating squat session at a time.

Self-administered forced reps: our squat motto is, “better to fail with integrity than succeed by breaking form.” Other squat school teach ways in which to slip and slide past squat sticking points: the easiest way in which to make squats easier is to make them “shallow,” barely dip down, barely bend the knees on each rep. This strategy could be summed up as, how do we “make heavy weights light,” whereas our philosophy is to use strictness, extreme ROM and other “intensity enhancers” in order to make “light weights heavy.” We say, don’t avoid sticking points, seek them out; slogging through sticking points is where the gains lie.

The dilemma for the athlete new to this weak-as-a-kitten stance width is how do I train? What do I do and how do I do it?

Initially, very few people are able to perform more than one or two super-strict ultra-deep bodyweight squats using the wider stance. The solution is not to shorten or “fudge” on the squat depth; rather than compromise on the technique, the solution is to squat perfectly but with assistance. How do we do that? We start with bodyweight squats and in order to attain perfection on every rep, give yourself as much “arm assistance” as is needed to enable you to perform a perfect squat rep on every single rep.

You might need to give yourself a little help, you might need to give yourself a lot of help, on some reps you might not need to give yourself any help – whatever is needed, to whatever degree, should be used to ensure that technical perfection is adhered to on each and every squat rep. We swear allegiance to the technique: poundage and muscle invariably comes in time.

- The self-administered forced rep: Stand in front of a vertical pole or in a door frame. Place the hands at waist height on the pole and squat down. At the bottommost point, sit erect and come erect; pull upwards with the hands with as much force as is needed to assist your thighs. Complete the assigned reps for the set. All the reps might need varying degrees of assist, but all the reps were technically perfect.

Perfect sets of five: the iron elite, top strength athletes, loves the five-rep set. A balls-to-the-ball set of fives strikes the perfect balance. At one extreme is the sarcoplasmic inflation associated with high, 10 to 15 rep sets. At the other rep extreme are the pure strength attributes associated by performing heavy triples, doubles and singles.

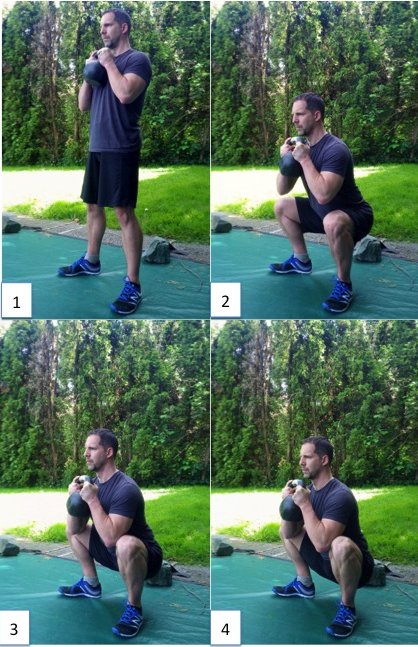

The kettlebell or dumbbell goblet squat: we seek to find the optimal stance that allows us to adhere to our bodyweight squat technical archetype. Over time we worked up to 3 sets of 10 perfect ultra-deep bodyweight squats. Time now to up the ante: a person could choose to continue down the rep road, perhaps work 3×10 in the bodyweight squat up to 3×15 and eventually 2×20. However, past 10 reps and we veer out of the realm of absolute strength and into the realm of strength-endurance; suffice to say, higher reps invoke a different physiological effect. Here’s how we break into “real” goblet squatting using poundage…

| Session | Payload | Sets and Reps |

| 1. | 10-pound dumbbell | 3 sets of 3 reps |

| 2. | “ “ | 3 sets of 5 reps |

| 3. | “ “ | 3 sets of 8 reps |

| 4. | “ “ | 2 sets of 10 reps |

| 5. | 15-pound dumbbell | 3 sets of 3 reps…repeat the process |

This is a basic periodization (preplanning) approach to squatting.

Goblet Squat Hell: making light weights heavy- a properly performed set of ultra-deep goblet squats will tax even the seasoned competitive back squatter. Goblet squat technique has to be exacting if results are to be optimal…

- Tuck the dumbbell or kettlebell tight under the chin and tight to the torso

- Inhale as you descend, initiated with a hip hinge and knee bend

- Do just free-fall, pull yourself downward, contract hams and glutes

- As you lower down and hit parallel, exhale, relax and sink further

- Maintain an upright (though relaxed) torso; don’t’ collapse forward

- Relax the leg muscles and allow the weight to push you downward

- Knees are pinned out, shins are vertical, torso erect, position is perfect

- Pause briefly

- Time to rise up out of the bottom

- Start the rep maximally relaxed and “pre-stretched”

- In the bottommost position, inhale, push down with feet, knees pushed out

- Transition from relaxation to generating maximal tension before movement out of the bottom

- Optimally, while arising, nothing changes except the upper thighs, opening the angle relative to the upright torso (ie the butt does not rise before the torso starts to move)

- The squat rep ends in a “hard” lockout at the top

The lifter then inhales and commences the next rep…

King Squat: The ultra-deep goblet squat, done deep and upright, will tax the mightiest of squatters: a good rule of thumb, a strong squatter, say a man capable of 315 for five reps, ultra-deep back squat without gear will be mightily taxed by a single 75-pound dumbbell in the 5-rep goblet squat. Let us ponder this for a moment and soak up the implications.

Riddle me this: a strong man is taxed maximally by goblet squatting a 75-pound dumbbell for five excruciating reps. That same man is taxed maximally front squatting 185-pounds for 5 rep and has to exert, all out, in order to make 255 for 5 reps in the hi-bar back squat. So here is the question – why bother to front squat or back squat? If all three squat variation are equally difficult, and, more importantly, that the results obtained from each is identical, then somebody please remind me why I am messing around with a 250-pound barbell on by shoulders?

If results from the three technically identical, equally taxing squat styles are identical, then henceforth why not just stick to ultra-deep goblet squatting with a lone, modest-sized dumbbell tucked up under my chin?

| Current Best | High-Bar Back Squat | Front Squat | Goblet Squat |

| 155 x 5 reps | 95 x 5 reps | 40 x 5 reps | |

| 205 x 5 | 115 x 5 | 50 x 5 | |

| 275 x 5 | 205 x 5 | 75 x 5 | |

| 315 x 5 | 255 x 5 | 85 x 5 | |

| 365 x 5 | 275 x 5 | 100 x 5 | |

| 405 x 5 | 315 x 5 | 120 x 5 |

These are realistic “spreads” between the three types of squatting; a balanced lifter executing their squats as technically intended will exhibit the balance shown above.

What if? So here is the tantalizing question: what if the man capable of (initially) performing 50 x 5 in the ultra-deep goblet squat, and ergo, is also capable of a 115×5 paused front squat and a 205×5 capacity in the back squat. What if, over time, that same athlete worked their goblet squat from 50 x 5 up to 100 x 5? Let us further assume the lifter works the goblet squat exclusively. Now here is the question: that lifter originally had lifts of 50 x 5 in the ultra-deep goblet squat and that level of strength normally indicates 205 x 5 in the back squat and 115 x 5 in the front squat. If he successfully works up to 5 perfect goblet squats with a 100, does that mean that he also is capable of 365 x 5 in the back squat and 275 x 5 in the front squat, all as a result of radically increasing his goblet squat capability?

Would that not be profound? We would be able to use smaller, much more manageable payloads in ways so clever and so excruciating as to be maximally effective. Why go to the trouble of handling a barbell quadruple in weight? If results are equal, I myself would prefer to wrestle with a kettlebell or dumbbell held in front of me, not on me or above me. If we need to bail mid-rep (it happens occasionally when you push with all your might) you simply drop the dumbbell or kettlebell on the ground in front of you.

If you do them right, on the final reps of a top squat set, it feels as if the blood in your veins is chemically transforming into gasoline and a spark ignites the gasoline; your veins have fire coursing through them, searing lactic acid sets the squatters thighs on fire. No pain, no gain! (That rolls off the tongue so much better than, “No discomfort, no hypertrophic-adaptive response!”)

Editor’s note:

Many of you may think the exhalation and relaxation at the bottom of an ultra deep goblet squat is technique sacrilege. Keep in mind that we are using very light poundage and any posterior pelvic tilt with exhalation at the bottom will not put you at risk of spinal injury, especially if you keep your torso vertical. The idea is to place you at a very mechanically disadvantaged position from which to start the squat ascent, at a depth most of you have not achieved at the bottom of a squat. A controlled ascent using pristine technique from this deepest of bottom positions is what makes “light weights heavy” and gives a potent neurological stimulus for growth with minimal risk of injury. Check your egos at the door and try the ultra deep squat cycle that Marty has prescribed starting with bodyweight only and progressing to the goblet squat. Going back to your traditional squat depth and technique after this program will seem like commutation of a life prison sentence. You will emerge stronger and more resilient.

***

Marty Gallagher is the author of Strong Medicine, The Purposeful Primitive and Coan: The Man, The Myth, The Method. Gallagher coached the United States team that won the IPF powerlifting world team title in 1991. He is a 6-time national masters champion and national record holder. He was the IFF world master powerlifting champion in 1992. He currently works with elite athletes, spec ops military and governmental agencies.