For the second MHS (Maximizing the Health-Span) post, I set out to write an article focused on intermittent fasting (IF). But, I quickly realized we needed a “first principles” foundation for context first. We need to understand the underlying physiological systems that are affected by intermittent fasting instead of taking a reductionist approach. A very simplistic way of thinking about the two major body systems most affected by intermittent fasting (and also training and other lifestyle choices) is categorizing them as systems of building and repair respectively.

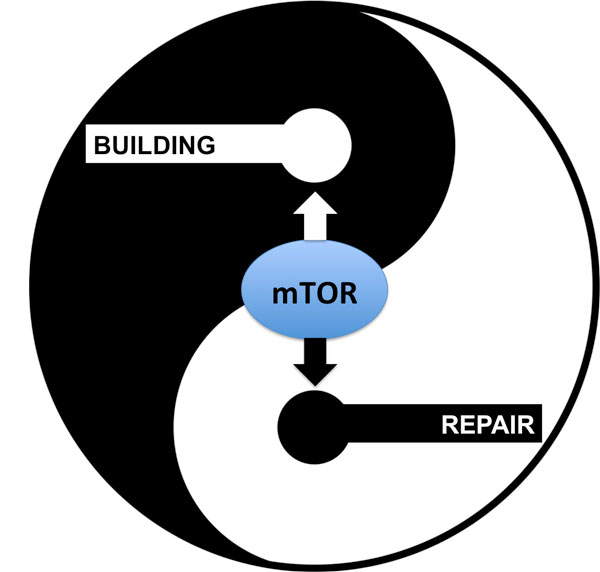

The body has to achieve a balance between building and repair at a cellular level. This balance will necessarily change depending on environmental demands such as physical activity and nutrition as well the aging process. Finding the right balance between building and repair at the right time is key to maximizing the health span.

At the center of the building and repair systems is a protein complex known as mTOR. The technical name for mTOR is the mechanistic target of rapamycin (formerly known as the mammalian target of rapamycin). mTOR functions as a molecular switch between building and repair.

Turning mTOR on promotes building. Turning mTOR off promotes repair.

BUILDING

Building (growth) is an anabolic process that happens when mTOR is turned on. Stimuli such as resistance training and eating protein (especially the branched-chain amino acid leucine) turn the mTOR switch on. The hormone insulin also turns on the mTOR building pathway. This effect of insulin should come as no surprise to readers of Strong Medicine (SM pages 107-108) as we discussed insulin as a hormone of growth and storage.

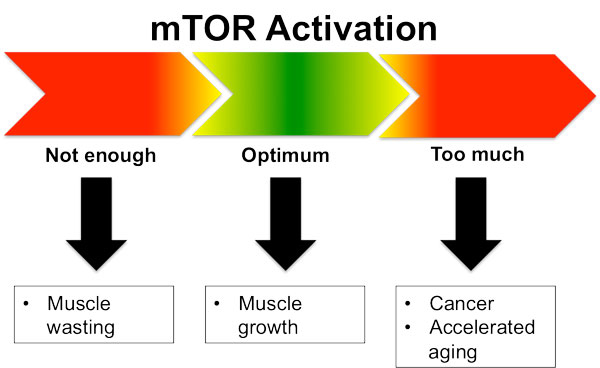

As Dan Cenidoza covered in his Strength after Sixty post, the anabolic pathways of building are crucial to grow and maintain muscle mass especially as we age. Not enough of “turning on” the mTOR switch can lead to sarcopenia and frailty in old age.

At the extreme end of the mTOR building pathway is cancer. By the simplest definition, cancer is uncontrolled cell growth. Recent science has shown that many cancer cells have abnormally high mTOR signaling, putting them is a perpetual state of growth. People with insulin resistance (SM p. 180) have higher levels of insulin in their bloodstream at all times which keeps the mTOR switch activated. Thus, it is no surprise that those with insulin resistance/diabetes are known to have increase risk of cancer.

We also now know that high levels of sustained mTOR activation can lead to accelerating aging in many species, including humans. With this information in mind, it becomes evident that getting the proper “dose” of mTOR activation is key.

We need enough “turning on” the mTOR building (growth) switch to prevent the loss of muscle mass so crucial for healthy aging, but no so much that we accelerate the aging process and become at increased risk for diseases such as cancer.

REPAIR (AND RECYCLING)

The opposite side of the mTOR coin is the repair and recycling system. This system is activated with the mTOR switch is turned off. The main process that carries out repair and recycling in our cells is called autophagy.

Autophagy literally means “self-eating.” Autophagy is the mechanism our cells use to recycle damaged proteins and cell machinery (including mitochondria) and use their parts to make new machinery and new sources of energy. Recycling old cellular machinery helps protect a cell from premature aging. This is similar to replacing a roof or hot water heater in your house to keep it functional as a dwelling longer. We can replace some of the parts for quite a while before having to buy a new house. Autophagy does the same thing for cells.

Autophagy is a cell-survival mechanism during times of stress. Fasting is one of the most common sources of cell stress that activates autophagy. Low protein intake and low insulin levels create a perfect environment for the mTOR switch to be turned off and autophagy to take over. Autophagy allows your cells to recycle used material for use as energy during stresses such as fasting, instead of breaking down valuable things such as muscle. Preventing catabolism (breaking down) of muscle is always a good thing!

By allowing recycling and repair within the cell, autophagy effectively extends the life span of the cell. This is one of the reasons why we seen increased lifespan with fasting and calorie restriction in animal such as mice and worms (it has not worked as well in humans as we will discuss in subsequent posts).

FINDING THE BALANCE

We know that turning on the mTOR building pathway in the right doses is crucial to maintaining muscle mass through the lifespan, a key to healthy aging. We also know that autophagy is a valuable process to extend the life and health of your cells. Finding the right balance between these two processes is where it can get tricky. This balance is also a moving target throughout our lifespan. We are going to use the concept of balancing mTOR activation (building) and mTOR deactivation (repair/recycle) to discuss training, eating, fasting, and lifestyle modification in upcoming posts. We will couple this with the concepts of hormesis and allostatic load (the Stress Cup) from Strong Medicine to create a framework to form a foundation from which to decide if practices like intermittent fasting have potential to maximize the health span.

****

Chris Hardy, D.O., M.P.H., CSCS, is the author of Strong Medicine: How to Conquer Chronic Disease and Achieve Your Full Genetic Potential. He is a public-health physician, personal trainer, mountain biker, rock climber and guitarist. His passion is communicating science-based lifestyle information and recommendations in an easy-to-understand manner to empower the public in the fight against preventable chronic disease.