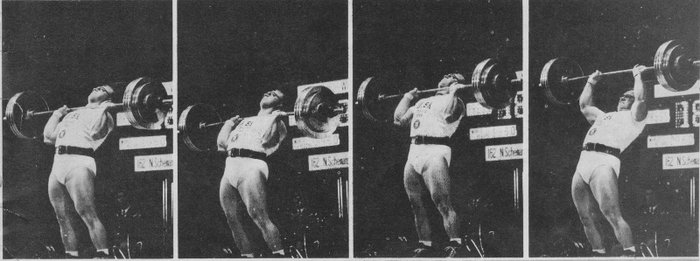

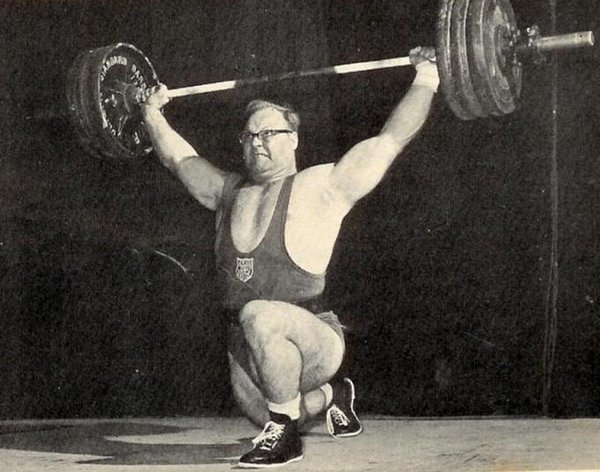

The press photo sequence above is of Ski pressing 396 at the 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games where he went on to take the bronze medal. He stood 5’11” and in this photo weighed a rock hard 260 pounds. At his awesome peak he was capable of a 420 press, a 370 snatch and a 460-pound clean and jerk. He could squat 650 for reps. Norb was the prototypical modern power athlete, both physiologically and psychologically. We want to relate (and embellish) a strength parable that was first told in Strength & Health magazine in 1966 by Bill Starr. The tale bears retelling because the lessons it aimed to teach are still valid in 2015.

The year is 1966 and a young trainee approached Norbert Schemansky—world and Olympic champion—with great trepidation. The Polish-American lifter from Detroit was infamous for brusqueness; he did not suffer fools lightly, particularly if he was interrupted when training. And at the moment Ski was training and not in a particularly jovial mood. The setting was the venerable and ancient York gym on a typical Saturday. Most every Saturday in the 50s and 60s, a mini-Olympic weightlifting competition was conducted in the York gym. The public was welcome and you could see a veritable cavalcade of national and world champion weightlifters in action. Lifting acolytes from around the country made their way to this American lifting equivalent of the Haj in Mecca. The vast majority of the onlookers were lifters seeking tips and tactics that would improve their own weightlifting efforts.

On this particular day, Norb was midway through the overhead press portion of his extended workout. An 18-year-old regional weightlifting champion had driven to York with two training partners. The young men were positively enthralled and agog, absorbing new data about lifting that they would use in their own herculean efforts; they could barely wait to return home and put into practice all the new training protocols and lifting techniques they had gleaned and observed. Our earnest protagonist knew that he and his pals would have to leave for home in the next hour in order to return in time to meet their parental curfews.

The youngster was bursting at the seams to ask Schemansky some pointed questions about tactics and training. The problem was Ski had been training for a long time and looked as if he might continue for quite a while longer. Under normal circumstances, the clean-cut young man would never bother Ski, or any other elite lifter while they trained. A training session was sacred, and amongst the Iron Elite interrupting the sacrosanct training atmosphere with mindless blather was considered sacrilege.

The youngster was impaled on the horns of an irresolvable dilemma: interrupt the fearsome Schemansky’s workout and risk incurring the legendary wrath—he’d been known to get physical with those who irritated him—or miss the opportunity to ask Ski questions. If his burning questions were left unanswered, it would haunt him forever. Summoning up his courage, the young lifter took in a sharp breath and strode to where the champ sat between sets on a steel folding chair.

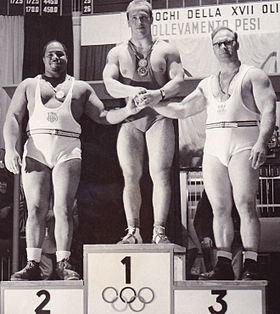

Ski caught the youngster approaching him out of the corner of his eye and thought, “Oh Hell no!” He mumbled and muttered under his breath; he knew what was about to happen. Schemansky was a month out from competing at the American National Championships; his last major competition had been the 1964 Olympic games, where he’d taken the 3rd place bronze medal behind the legendary Soviet world and Olympic champions Yuri Vlasov and newcomer Leonid Zhabotinsky. An uncontrollable scowl spread across his already dour face as the well-built boy pulled up to a halt four feet in front of Ski and stood wordlessly at attention. After a long silent pause, the youngster said in a single breath…

“Mr. Schemansky, Sir! I am sorry to interrupt you, my press has been stuck at 205 for the past six months. Could you be so kind as to give me some advice about how I might increase my press?”

Ski exhaled a cooling breath and proceeded to talk himself out of the trees; he was NOT going to go off, explode, or go ape-shit on this earnest young man. Ski was trying to turn over a new leaf and would not resort to cussing this kid out—as he would have in the not-too-distant-past. Truth be known, as Ski looked the kid up and down like an expensive side-dish he hadn’t ordered—despite wanting to hate all interlopers—he got a good vibe from the boy.

Ski had a secondary motive: despite the pure joy he derived from going off on a civilian, any emotional outbursts—while terrifically satisfying (a guilty pleasure)—would derail and destroy the workout. He had eleven training sessions before leaving for the national championships and every single session needed to count; each week he had to show tangible improvement.

He decided to be tolerant and understanding with this clean-cut polite boy—no yelling, profanity, or rebuffs; he would avoid ‘leaking’ any of his precious emotional psych. Plus there was something oddly endearing about the bearing, manner, and presence of the youngster who stood in front of him. The boy was deferential and reverential, akin to a young soldier addressing a general. Ski always and forever had a place in his heart for the military man so he grunted a reply…

“FIRST OFF it is RUDE to interrupt a man prepping for a national championship—WHAT is so GODDAMNED IMPORTANT!”

Schemansky was pleased with himself. He considered that a measured response and quite restrained, compared to previous “alleged” incidents. The boy literally quaked, shook, and was on the verge of peeing himself; his training partners slunk backwards four steps. Norbert then switched gears and said,

“Son, if you want to improve your press—PRESS!”

Ski deliberately made eye contact with the youngster. A look of confusion and consternation spread across the boy’s face. Puzzled, but elated by the fact that he had not been physically assaulted, the youngster decided to press his luck and posed a second question.

“Mr. Schemansky, sir! Any suggestions on how to improve my snatch would be greatly appreciated. I have been stalled…”

Ski decided to reinforce a point. “Do I look like a give a Tinker’s damn if your snatch is stalled?” It was a rhetorical question. “If you want to improve your snatch THEN SNATCH!”

The rugged champion leaned back in his chair and drilled his eyes into the youngster until the boy winced and wilted. Yet, instead of skittering away, the youngster gathered himself admirably; he knew he was pressing his luck, but plunged onward anyway. “How about my clean and jerk, sir? Please sir, my jerk stinks and yours is great—no, incredible—what can I do to improve my clean and jerk, sir?

“More Clean and Jerks, son!” Norb was warming to the kid.

“Squat?”

This actually made Norbert laugh. The boy had big balls. He looked at the boy and with a quick jerk of the head wordlessly indicated that the audience was over. The boy, being smart and perceptive got that he was being dismissed. He wanted to express his gratitude for the great man’s time.

“Thank you sir.” He extended a limp, damp hand that hung there suspended in space for the longest time before Ski sighed and engulfed the boy’s hand with his own callused hand and gave the youngster a real man’s handshake, a small jolt, just a taste of his raw power, transmitted through a crushing handshake. The boy winced in pain. He would remember those 15 minutes for the rest of his life.

50 years later the strength elite would still talk about and marvel at the Zen wisdom and sparse economy of Norb’s precise answers. There was (and remains) so much truth in his advice.

There is a famous Zen Koan: “What is the sound of one hand clapping?” The answer is a hard slap across the face. The student poses the question and the Roshi slaps the taste out of the acolyte’s mouth. Often that unexpected slap would jolt the Zen student out of his conscious mind, allowing him to attain the level of consciousness that cannot be reasoned out. Ski’s irreducible answers were akin to the Zen face slap.

Truly, as Ski succinctly noted, if a man is serious about improving his press, snatch, clean and jerk, squat, deadlift or any other major resistance training exercise—the best possible way to improve is to do that specific lift—repeatedly. Remember Aristotle’s truism: “We are what we do repeatedly.” Sport specificity applies to strength training movements. As my old lifting coach Hugh Cassidy would say, “The best way to improve in any lift is to do that lift and do it a whole lot.”

Further, the best assistance exercises (adjunct lifts) for any of the three powerlifts most closely resemble the core lift. Hence, the best assistance exercise for bench press is the bench press with a wide grip or a narrow grip; in keeping with Cassidy’s timeless axiom, variations on flat benching are superior assistance exercises to say, incline bench press or decline bench press.

There is tremendous wisdom hidden deep within Schemansky and Cassidy’s pithy pronouncements. Schemansky classic power strategy for improving strength could be described as “doing fewer things better.” This old school philosophy could be summarized as, “Perform the major lifts and do them often—and do very little else.” Old pros knew that a universe of variety and variation exists within the core four lifts and their assistance-lift brethren.

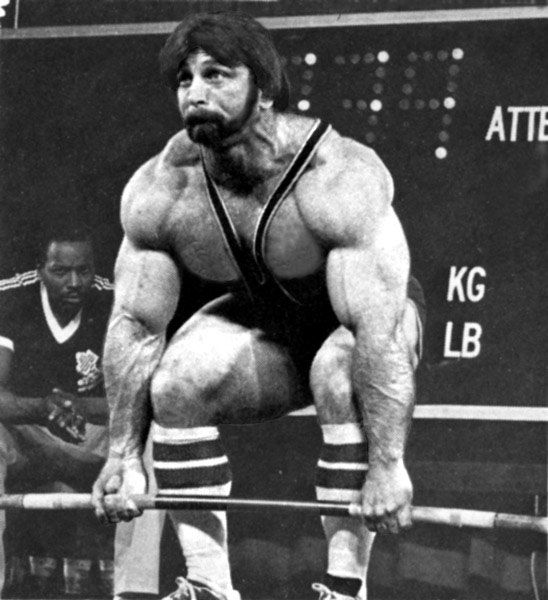

In this day and age, it is very chic and fashionable to avoid doing the lifts. The prevailing wisdom in our information age is that you can improve the squat, bench or deadlift without doing the actual lifts. You can get just as strong, stronger in fact, by using bands, boards, chains, board presses, box squats—anything to avoid the harsh starkness of that most primal and ancient of strategies… “Just do the lifts.” Ski and Cassidy (and John Kuc, Jon Vole, Kaz, Pacifico, and all the other all-time greats of the 1960s and 1970s) would do the three Olympic lifts or the three powerlifts—and little if anything else. It would never occur to these powerhouse men NOT to do the core lifts.

How did we arrive at this upside-down bizarro world? It think it is no coincidence that the physiques of Doug Young, Kaz, Gamble, Cash, Roger Estep, and all the other muscled-to-the-max men of yesteryear blow away the physiques of today’s “smarter” athletes. The ancients bore the weight, embraced the sticking points, and did full and deep lifts. They performed the ultra-basics over and over and over and over, ad infinitum, ad nauseam. How do you get really good at doing the core lifts? By doing them repeatedly, world without end, amen.

Lift performance, the classical report card, has been inflated through the use of supportive gear, the mono-lift and corrupted judging. It appeared that lifts were skyrocketing and all as a result of this get-better-at-the-lift-without-doing-the-lift philosophy. Actually, if you strip the modern lifter of his lifting apparel, make him do below parallel squats and bench presses without wearing the bench shirt, then guess what? The modern “athlete” is weaker than the ancients. Talk about an inconvenient truth…

Ski and Cassidy, Rigert and Pacifico, Mel Hennessey and Roger Estep knew that in order to get really good at a thing, you needed to do that thing, endlessly. By doing the lifts to near exclusion, they built physiques and levels of raw power and strength which are unrivaled and unmatched to this day. Those lessons have been lost to history: in our age, everyone is looking for the next new thing. However in the universe of radical physical transformation—more muscle, more strength, more power, radically reduced body fat percentile—the answers lie in the deep and primal past.

The smart trainee needs to look backwards for breakthrough strength strategies; back to the ancients and their “plain vanilla” training strategies that relied more on effort and degree of difficulty than in sophisticated user-friendliness. These stark, barebones training strategies discovered by the ancients need to be resurrected. Those who tell you that modern strength and power strategies trump what came before are false prophets speaking with forked tongues. It is time we destroyed the golden calf of delusion and get back on the Old School good foot: to get super-strong become super-simplistic.

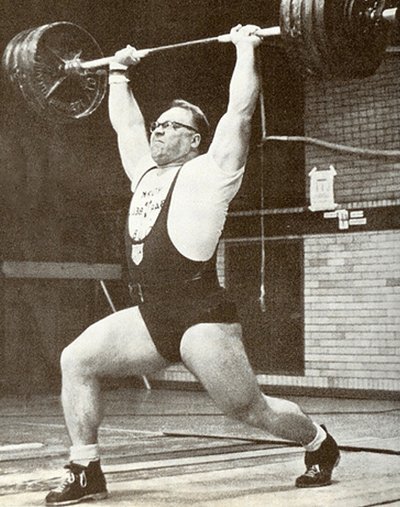

Norb Schemansky was born in 1924. The Detroit native learned his fundamentals early. He came into his own during the post-war period. Norbert stayed at the top of the strength world from the 1940s all the way into the late 1960s. He cut his teeth on simplistic pre-war training templates and over time modified them; he grew larger and stronger as he got older. Norb set the world record in the snatch, 363lbs at age 38, some twenty years into his competitive career. Norb adapted and adopted, yet he always retained the simplistic sophistication that earmarked his training strategies. Even as he matured, he never lost his pre-war, depression-era work ethic.

Norb become the first weightlifter in history to earn four Olympic medals, despite missing the 1956 Olympic games due to back problems. Norbert won an Olympic gold medal; a silver medal and two bronze medals spread over four games. He won the world championship three times and won the Pan American Games. He was the Olympic champion in 1952. He set an all-time world record in the snatch in 1962 when he split-snatched a seemingly miraculous 363-pounds. Norb set 75 national, world, and Olympic records.

According to his biographer Richard Back, Schemansky related that the most impressive feat of strength he ever witnessed took place at the 1952 Helsinki Olympic Games during a rare joint training session when the American and the Russian lifters were both in the same training hall at the same time. Trench-coated KGB secret police lined the walls of the training hall just in case a desperate communist athlete dared try and dash for sanctuary and freedom. This stuff was real and Ski saw the Big Red sport machine up close and personal for decades.

Ski’s number one competitor in 1952 was the 180-pound Soviet champion Gregory Novak. Novak held the press record at 309 pounds and during the joint training session the stumpy, thick Russian effortlessly pressed 281 pounds, and then—no doubt for Norbert’s benefit (Novak was well aware that Schemansky was watching)—pulled a psych maneuver that blew Ski’s mind.

“First he presses 281 and I am impressed with the strictness and lack of backbend. I mean back then (1952) a press was still a press.” Norb then related, “Then, just for the hell of it, Novak lowers the 281 pound weight down behind his neck and presses it three times! I’m thinking, I better have a damn good snatch and jerk because I surer than hell was not going to beat this beast in a pressing contest.”

Schemansky struggled with life outside of weightlifting. He stayed in Detroit and was reduced to working minimum wage jobs to make ends meet between national and world championships. While Big Daddy Hoffman would cover the expense of sending Norb to the national and world championships, between those trips and excursions Ski had to pump gas and scrub toilets. It became so bad that Sports Illustrated magazine ran a feature article called, “Looking for a Lift,” an expose’ on the hard times that had befallen one of America’s premier Olympic athletes.

This wasn’t some retrospective on how some former great was now laid low—Norbert was on the national, world and Olympic teams at the time, winning and placing at the highest levels of the sport. In the SI magazine photo, Norb stood desolate, wire scrub brush in hand in front of a commode he was about to scrub. This was a MAN, a man with a wife and kids who in his spare time was kicking ass internationally for his country. At home he was a pathetic nobody, always two paychecks away from disaster, destitution and homelessness.

Despite the feature in SI describing his plight, no sugar daddy, organization or corporation stepped forward to offer Ski any relief. In nearly every retrospective written on him, the phrase “bitter” enters into the article. Ski was once asked what he was most bitter about and he wryly commented he was “bitterest about always being portrayed as bitter.” It was yet another one of his barbed comments about an athletic career that was nothing less than astounding contrasted with compensation nothing short of pathetic.

Indirectly, Norbert heavily influenced the fledgling sport of powerlifting. Norbert trained in Detroit with a young engineer named Glen Middleton. When Bechtel transferred Middleton to Washington, DC, Glenn sought out and began training with Hugh Cassidy. Hugh was taken with Middleton’s urbane sophistication and his intellectual approach towards strength training. Hugh, another intellectual with a first-rate brain, appropriated the essence of the Schemansky approach—a simplified exercise menu, ferocity in training, singularity of purpose, preplanning (a revolutionary concept at the time) and the idea that over time a lifter needed to grow more muscle.

Ski rose to national prominence as a 180-pound lifter and finished out his career weighing a massive yet lean 260 pounds. Hugh took the lessons learned from Ski, via Glenn, added his own empirical-based technical and tactical modifications and won national and world championships. In turn, he mentored national and world champions. Cassidy’s teachings were passed to me and I passed them along to others. In turn, I created world champion athletes who set all-time world records using these primal Ski/Cassidy techniques and tactics.

We need go back to the future and revisit the methods of Iron Immortals; their simplistic, primal approach towards transformational strength training is so much more effective and applicable for today’s time-pressed individual than the “revolutionary” power and strength methods pedaled by modern day fitness hucksters seeking to turn a profit. As my own cliché goes: There is no school like Old School.

***

Marty Gallagher is the author of Strong Medicine, The Purposeful Primitive and Coan: The Man, The Myth, The Method. Gallagher coached the United States team that won the IPF powerlifting world team title in 1991. He is a 6-time national masters champion and national record holder. He was the IFF world master powerlifting champion in 1992. He currently works with elite athletes, spec ops military and governmental agencies.