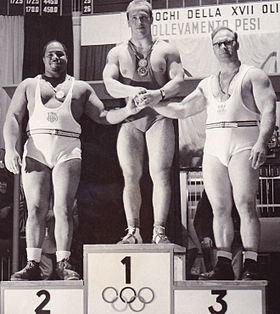

I stopped coaching at the national and international level when my superstar powerlifter, Kirk Karwoski, retired in 1996. After a ten-year rocket ride with the Kirk, the undisputed King of powerlifting, anything subsequent would have been anticlimactic. Kirk crushed the best with yawning nonchalance: he won seven straight national titles in three different weight divisions. He steamrolled to six straight world titles and set 20 + world records, including an all-time squat record of 1,003 pounds that remains unsurpassed to this day, 18 years after being set. He was widely considered to have had the strongest legs in the history of powerlifting and he built his unprecedented leg power using a strength system I introduced him to. He and I, coach and athlete, refined and fine-tuned this simplistic approach over the next decade. With each succeeding year he got substantially better.

We called our power approach “The Modified Cassidy” because this unique strength strategy was based on an approach first devised by world champion Hugh Cassidy. Hugh’s template was brutal yet effective, a minimalistic approach towards strength training (and eating) that we customized for Kirk. We were heavily influenced by innovative modifications made to the same system we used by power immortals Ed Coan and Doug Furnas. I talked to Coan weekly for years; we were like two lab scientists discussing a mutual science project—which happened to be Kirk. He was the baby gorilla we were raising in captivity: each week I would tell Coan what Karwoski had done in training and listen to Ed’s feedback. We had this ongoing three-way conversation and eventually settled on a system that caused Kirk to skyrocket. It took five years of dues paying before Kirk won his first national title. That same year he took second place at the world championships when Kristo Vilmi of Finland, edged him by 5-pounds. After that, Karwoski went on a rampage: Vilmi was the last man to beat Kirk, ever.

Kirk and I were a coach/athlete partnership: we thought long and hard each successive competitive year about what new wrinkles we would add, what modifications we would apply, how would we hone and refine our core strength system to make it better. We had a viewpoint, a philosophic strength strategy and our report card was how we did at the national and world championships. For seven years he was the best in the world—by a country mile. He didn’t defeat the competition; he annihilated the competition. He was our champion and we campaigned a specific method, a defined strength philosophy. Kirk was the best in the world for a long, long time and he could have won five more world titles had he not become bored with it all.

I did a lot of coaching at nosebleed levels, including coaching the United States to the IPF world team title at the 1991 world championships in Orebro, Sweden. Like Kirk, I too got burnt out. Truth be known, I didn’t miss coaching. I did so much of it for so long and with such a high caliber of athlete that the idea of coaching again held zero appeal. That all changed when I got a load of Cristi Bartlett. Naturally I heard about her before I met her. She was a protégé of Jim Steel, the no-nonsense, Old School, hardcore strength coach at University of Pennsylvania. Jimmy has been at Penn going on 15 years and oversees a 20-million dollar facility with responsibilities for twenty + collegiate sport teams. He needs help and Cristi worked for Jim as an assistant coach. He began telling me about her years ago and a few years back I met her.

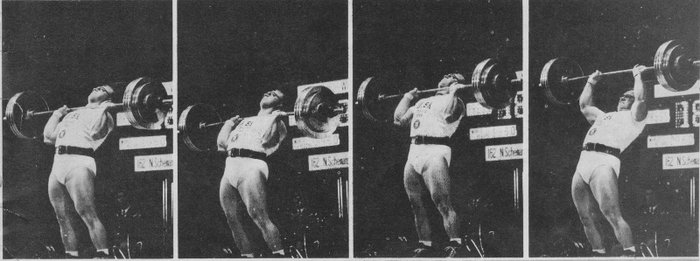

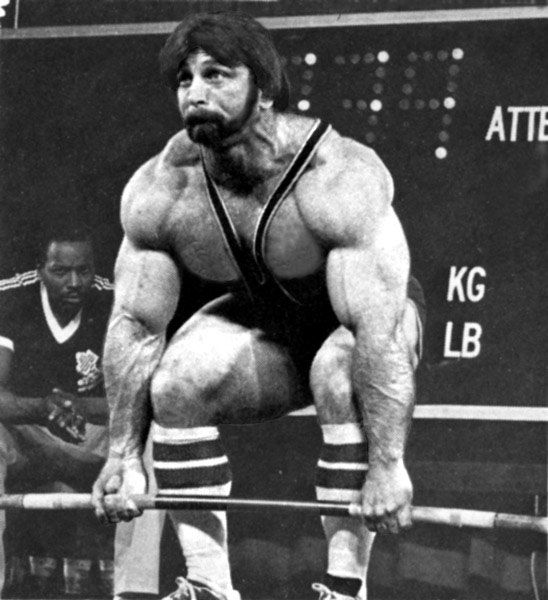

I was really impressed with how she looked and how she moved. She was a muscled-up 190-pounds, which sounds huge, but on her it looked quite normal. She moved like a panther and had “elite athlete” stamped all over her. I was hardly surprised when told she’d been a collegiate basketball player and held a Masters degree in exercise science. Cream rises to the top and genetics, brains and youth are always a good combination in an athlete. While I was not surprised at her athletic pedigree or academic degree, I was quite surprised (shocked, actually) at how “spot-on” her deadlift technique was: she deadlifted as if she’d come straight out of the same Hugh Cassidy technical deadlift boot camp that world champions Mark Dimiduk, Mark Chaillet, Marty Gallagher, Kirk Karwoski and Don Mills were schooled in.

She had intuitively taught herself how to pull using the same technique we were taught: narrow stance, upright torso, bust it from the floor using leg power, finish off the pull with a steel-coil hip hinge held in reserve until that special instant. “Where’d you learn to pull like that?” It was the first question I ever asked her. “Oh, I sort of figured it out on my own. It seemed logical.” Now that was the right answer. She had excellent body proportions; a positive indicator for future balanced lifting. Most good female powerlifters are short and squat; they usually have good squats and good bench presses and are piss-poor deadlifters. Cristi is the rare breed: world level bench presser and deadlifter. She is also a 100% lifetime drug-free athlete.

I asked around a bit about the national and world records in the newly minted USAPL and IPF “raw” divisions. Raw powerlifting is done without any supportive gear, other than a weightlifting belt. The explosion of CrossFit has been a shot in the arm for raw powerlifting competitions. Nowadays the raw national championships might attract 400 + lifters. The USAPL and IPF are strictly judged; squats have to be below parallel; and they practice out-of-competition drug testing. Strict judging and strict drug testing work in Ms. Bartlett’s favor. Her training lifts were at or above world record level. For the first time in decades I sensed that here was an athlete capable of going all the way: become the best in the world. Few knew those “all the way” ropes better than me.

She was receptive to the idea of going to the USAPL national powerlifting championships. That competition would be held close by, in Scranton, and would occur in October, a long time off. We agreed in principle to “go for it.” She needed to compete in a qualifying meet in order to be eligible to compete at the nationals. We found a USAPL competition in suburban Baltimore on July 12th and worked together for eight weeks leading up to the Baltimore competition. The web is a wonderful training tool: each week she would video tape her “top set” in the squat or deadlift and e-mail it to me. I would review it, critique it and then, based on all the combined factors, we would make the poundage/rep call for the subsequent workout. It was agreed that the key to her ultimate powerlifting success would be lie in increasing her leg strength.

She was already world level in both bench pressing and deadlifting but she was 100 pounds off the pace in the squat. Champions don’t continually play to their strengths; instead they attack their weakness. That is where the dramatic improvement lies. Ergo, it only stood to reason that she would concentrate on bringing up her squat: to do so would make her invincible. Rome would not be built in a day and we would treat the Baltimore meet as a mere workout, she would lift conservatively: no close misses.

The actual competition turned out to be a madhouse as 100 lifters were lifting. The 28-year old exhibited coolness in her competitive demeanor; she was aggressive yet upbeat, engaged but unfazed, she was alternately in one of two states: totally relaxed sitting in the audience with her dad and Tracey, her training partner, or prior to a lift, concentrated and focused. In her squats, her first attempt was with 295-pounds and she buried the lift a full three inches below parallel. It was a “three-white-light” success. Her 315-pound second attempt squat was easier than the first. She roared out and methodically dispatched a perfect 3rd attempt with 330. Each squat was a cookie-cutter replication of the previous perfect squat.

In the bench press she was nursing a shoulder injury, a serious injury that caused her to train light. She was not at her benching best. The competitive bench press has to be paused on the chest and then pressed evenly and perfectly: she perfectly pressed 205, 231 and finally a very easy 248. We were unaware that the national record was 252-pounds, or we would have taken 256 on her 3rd attempt. Six lifts, three squats, three bench presses, eighteen white lights; she was perfection in motion.

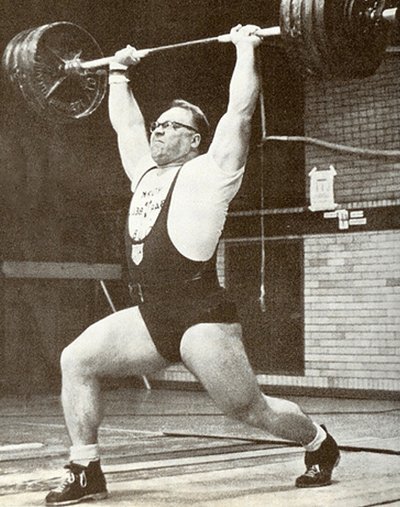

In the deadlift, she hit her first (and only) snag of the day when on her 1st attempt deadlift with 440-pounds she drew a lone red light; the side judge said she did not have her shoulders all the way back at lockout. Two judges passed the lift. She asked for 485 pounds on her second attempt deadlift. The current national record was 473 pounds. After seeing the slump-shouldered 440 opening deadlift, I secretly thought 45 pounds might be a bridge to far. Plus the competition was dragging on and on and cumulative fatigue was a real factor; Cristi had taken her first squat warm-up at 9:30 am and now it was 2:30 pm. That is a long time to maintain an edge.

To my surprise and delight, she strode out and after a long, hard pull locked out 485 pounds to set the new national record. What a GRIP! Mark Chaillet had the strongest set of hands I’ve ever seen and he could just tug and tug and tug on an 850 + pound deadlift all day long—Cristi has that same powerhouse type of “kung fu grip.”

After she locked the weight out and accepted the thunderous applause, she came off stage and I congratulated her. “That’s it—right? You don’t want a 3rd do you?” After seeing how tough the 485 was, after seeing the adrenaline dump and the excitation of that national record, I was convinced she was done. “Whoa!” she said, “How about a 3rd attempt?” I was puzzled, “Really?” I looked deep in her eyes; she was smiling but serious. I didn’t say it but thought; if you worked that hard with 485, what are we going for on the 3rd, 486??? “Sure!” I said, “What’s the number?” She didn’t hesitate. “500!”

She would need to find a deeper well somewhere. To make a long story short, it was as if everything in the competition leading up to this point was the preliminary stuff. By now it was apparent to everyone in the oversized, stuffed to capacity gym, that this woman, pound for pound, was the best lifter in the entire competition, female or male. This deadlift would be more than the male class winner in the 184-pound class and it would exceed her just-set national record. It would also exceed the current 496-pound IPF world record in the deadlift.

She crushed 500. 485 was light years better than 440 and 500 was light years easier than 485. She had racked up nine perfect lifts and made 26 out of a possible 27 white lights. She ended with a world record-exceeding lift in her second-ever powerlifting competition. It was exciting as hell. It triggered a feeling in me I hadn’t felt since Kirk hung it up. As my old boss at the Washington Post, Vic Sussman used to say, “Let the facts speak for themselves.” Here is a fact: Cristi Bartlett got me back into coaching…and I am excited to see how far she can go. If she caught fire she could become the female Ed Coan, she’s that talented.

***

Marty Gallagher is the author of Strong Medicine, The Purposeful Primitive and Coan: The Man, The Myth, The Method. Gallagher coached the United States team that won the IPF powerlifting world team title in 1991. He is a 6-time national masters champion and national record holder. He was the IFF world master powerlifting champion in 1992. He currently works with elite athletes, spec ops military and governmental agencies.