“We here in the Western world are top-heavy. ‘Shoulders back! Chest out! Stomach in!’ Thus the center of gravity becomes elevated. In zazen, Zen training, the tanden (or hara) is the source and foundation of deep meditation. When moving, the tanden is the source of bodily strength. Abdominal breathing generates strength: we live from this centremost point of gravity. This is Zen breathing. Sekai tanden means spiritual field. The tanden is located below the navel. Here, in the Western world, we don’t think in terms of having a singular point of gravity, a vital center; in Zen this vital center is our wellspring source.”

Tanden: Source of Spiritual Strength, Kongo Langlois, Roshi

Since 1970 I have been pondering this odd oriental concept of “the body’s singular point of gravity.” Why was this concept so important in meditation and certain martial arts? This exact center of balance even has a name; it is called the hara, or tanden in Japan, in Chinese medicine and Taoist martial arts the exact same thing is called the dantian. Conceptually, the idea was to initiate the breath from that epicenter of balance. This center of gravity exists within every human body at all times. Whether we are aware of (or attuned to) this bodily gyroscope is another matter entirely.

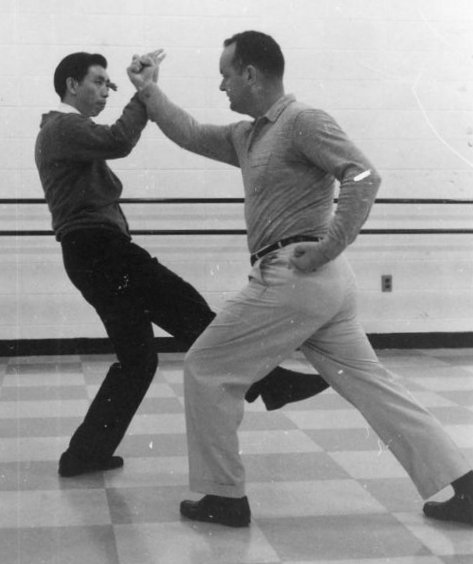

I got some high level schooling from an elite martial master very early on. I was first trained in dantian breathing when as a 20 year old, I began five years of study under America’s foremost expert on the Chinese “internal” martial arts, Robert Smith. Bob was, at the time, 50ish, a famed author, a hardcore judo man, a former CIA station chief, a sophisticated yet earthy man fluent in several Chinese dialects, brilliant, funny as hell, ingratiating and never off-putting. He was an amazing dude that just happened to live in my neighborhood.

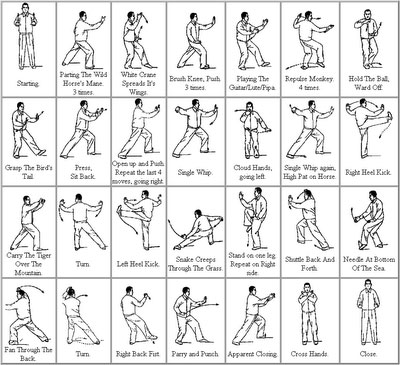

I trained with him twice a week for many years. After each session I took home what he taught me to work on in lone solo sessions. On Thursday night and Saturday morning he taught me the three interrelated internal martial arts of Pa kua, Hsing I and Tai Chi. Bob Smith was singlehandedly bringing attention and western scholarship to these obscure fighting styles.

During our training sessions he would talk endlessly and incessantly about the concepts of “rooting” and “sinking,” and “breathing deep and low from the dantian.” He preferred the Taoist phrase and would place his hands on his own lower ab area and make it throb to demonstrate that his “chi” breathing originated at his “exact center of balance.”

Even during the execution of lightning fast, highly exertive Hsing I katas, he expected the athletes to attain, maintain and retain deep abdominal breathing; nose breathing went out the window with the fast and intense stuff as we couldn’t pull in enough oxygen (using nose-breathing) to forestall oxygen debt and the resultant lactic acid build-up. Though we had to breathe through our mouths, we were still expected to use diaphragm breathing, though no one called it that back then. Linking the concentrated breathing with form and movement was far easier to successfully attain when engaging in slow-motion tai chi.

While I preferred the dynamic and circular Pa Kua and the slashing and linear Hsing I, I found it far easier to get “into the zone” and successfully sync deep and concentrated breathing with precision glide-path tai chi. I would practice alone in my basement and would repeat the first third of the 36-posture sequence endlessly; I would really get lost in the whole thing and eventually I “got it.” I knew I had gotten it when one day (a year in) he looked at me and did a double-take. He laughed, “Hey, you got it!”

Smith was a famed writer, a great writer in fact and a huge influence on my emerging writing style. He was a fabulous alpha male role model: smart, a genuine bad ass, simultaneously erudite and streetwise, he was formidable but approachable. He put me in mind of a soldier of fortune character out of a John LeCarre novel set in Hong Kong. He was getting a kick out of teaching earnest locals right in his own backyard and he had the writer’s ability to communicate verbal concepts with crystal clarity. Vladimir Nabokov once marveled, “To me, spontaneous eloquence is miraculous.” When Bob Smith instructed you, it seemed miraculous.

I learned all about rooting my feet, sinking and relaxing. I learned to breath in such a way as to expand my “orb of chi.” Regardless if we were “walking the circle” in Pa Kua, throwing the “five fists” in Hsing I or floating across the landscape using his sublime tai chi style, we were always expected to be breathing from the “expanding and contracting” dantian.

Before each training session, as a group we would stand at relaxed attention, performing “quiet standing” with our heels together, sinking down into the soles of the feet. We focused on the mechanics of breath. He would speak to us as we stood in mute, relaxed, erect, alert attention…

“When Cheng Man-Cheng accepted Ben Lo as a student he made the youngster do quiet standing—and nothing else—for one hour each day seven days a week for one year. Why? This is a rhetorical question so please allow me to answer: the Master was teaching the neophyte about root and about how to truly relax and really sink and how to access dantian breathing. At the end of the year Cheng taught Ben the actual forms and Lo mastered all of them effortlessly and quickly. When asked how this was possible Cheng said, ‘Because all the hard and important work was done that first year.’”

Smith was an expert explainer of the concepts that prefigured technique…

“Imagine a steel rod running through your body at hip level. One end of the rod starts at the absolute center of your right hip joint. A thin chrome rod runs through your abdomen and ends in the exact center of your left hip-joint. Now imagine that at the absolute epicenter of this thin steel rod that runs right through the middle of your body, that there is a round chrome orb, a ball the size of a golf ball. As you inhale this orb swells to the size of a tennis ball. As you slowly exhale, the tennis ball-sized orb shrinks back down to the size of a golf ball. This is your dantian powering the breath process.”

I loved that image. It enabled me to conceptualize was being asked of me: I could attain low breathing via the dantian because I now understood it and could mimic the image using his imaging. Smith would pace between our rows, talking to us as he inspected our quiet standing posture. He would stop to make minute adjustments to our shoulder or arm position. I remember him always adjusting my elbows. His voice sounded like Charleston Heston playing God…

“Expand the waistline outward in a level and even fashion…push the bottom of the belly downward…actually you create a vacuum effect, similar to the downstroke of a piston drawing fuel into the cylinder of an internal combustion engine…pull the breath into the body with mouth closed…pull air in through the nostrils. Listen to the sound, the noise the air makes around the nostrils. This requires close attention.”

You could hear a pin drop as he talked us into breathing just right. Unbeknownst to us, he was also maneuvering us into a placid headspace.

“Contemplate the breath with the care and attention it deserves…observe it with complete focus on both inhalation and exhalation. No need for thinking or thoughts…breath deep and low from the dantian…relax…sink…stay focused please. No passengers, everyone is a participant.”

He was the personification of Nabokov’s spontaneous eloquence; he said things that I have never heard said before or since…

“Pay particularly close attention to the breath at the ‘turnarounds,’ the little dead space that appears in short gap at the end of each breath, that transitory instant when inhalation becomes exhalation and again when exhalation becomes inhalation. Stray thoughts love to slip into these crevices and attach and germinate and take root inside these tiny gaps of inattention…every breath has four parts: inhalation, turnaround, exhalation, turnaround; draw the breath from down deep, using an expanding and contracting dantian to power everything.”

He could tell when a person had lost focus just by looking at their posture.

“If you engage in internal conversation, you ruin the quiet standing effort. If a stray thought arises, note it and let it pass by. Just because a thought drops by doesn’t mean you have to invite it in for a cup of coffee.”

When he was satisfied that we as a group had the requisite focus, he would set us in motion; guiding us through the circles and “palm changes” of Pa Kua, the straight-line power slams of Hsing I or his unique and stylized brand of tai chi, with its combination of grace, power, flow and relaxation. He had specific techniques for each posture and every transition. He was a superstar in that world.

Diaphragm breathing is a relatively popular topic (deservedly) in the world of high-level fitness. This strategy has deep roots in meditation and martial arts. In formal Taoist, Zen or Hindu meditation, deep breathing, low breathing, is always a foundational technique and a core principle. Breath and mind always seem to walk hand in hand. Where there is meditative breathing invariably and quite naturally (and not coincidentally) “mindfulness” invariably appears.

There is tremendous interest in the subject of mindfulness. Almost without exception, mindfulness books, articles, strategies and tactics emphasis some type of focused attention on the mechanics of breathing. To be able to concentrate fully and completely on breath for an extended period is the surest way to attain true mindfulness. But there are pitfalls: as someone noted, “Mindfulness has become the new folk religion of the secular elite.” It seems everyone everywhere has leapt on the mindfulness bandwagon.

For those of us that have been on the mindfulness bandwagon for decades, our initial amusement at its newfound popularity has been replaced with successive emotional phases of puzzlement, befuddlement and repulsion. The repulsion comes from the ultimate awareness that money and financial gain have successfully corrupted and diluted the effectiveness of true mindfulness. Mindfulness-lite is watered down, user-friendly, anemic and ineffectual. But the ease of the method and the wildly exaggerated promised results makes faux mindfulness eternally popular.

We were mindful before mindful was hip. We achieved our mindfulness without striving for it; it was a by-product of what we were after: improved performance in the martial arts. Our mindfulness was attained by focusing 100% of our attention on the mechanics of breath. In our meditational sitting, during our quiet standing, or while performing martial katas, we focused on breath with every fiber of our being. In doing so we become mindfulness personified.

A smart trainee expropriates Smith’s concept of the physiological epicentre, the expanding and shrinking dantian orb. Use this image to find your physiological center of balance. Sync breath with posture and simultaneously acquire the mindfulness mindset. How appropriate that Smith’s ancient martial strategy of “breath before everything” turns out to be the perfect gateway into modern mindfulness. The fact that his forgotten lessons are still relevant and important seems weirdly appropriate. I am happy to pass along even a sliver of his iconic wisdom.

Mr. Smith joined the U.S. Marines in 1944 at age 17, served overseas in the Pacific theater with the Fifth Division as a combat rifleman at Peleliu and Guam. He was among the first troops into defeated Japan. Mr. Smith received his undergraduate degree in History from the University of Illinois and his master’s degree in Far Eastern and Russian Studies from the University of Washington in Seattle. In 1955, he joined the CIA as an intelligence officer, going to Taiwan four years later in 1959. There he continued his pursuit of martial arts practice and research. During this time he went to Tokyo and won his third degree black belt in Judo at the Kodokan, the international Judo headquarters.

***

Marty Gallagher is the author of Strong Medicine, The Purposeful Primitive and Coan: The Man, The Myth, The Method. Gallagher coached the United States team that won the IPF powerlifting world team title in 1991. He is a 6-time national masters champion and national record holder. He was the IFF world master powerlifting champion in 1992. He currently works with elite athletes, spec ops military and governmental agencies.