This is the second in a series of articles developed from Dr. Chris Hardy’s live presentation at Dragon Door’s Inaugural Health and Strength Conference. Click here to read the first article of the series.

The Stress Cup is a visual representation of allostatic load, the total amount of stress. In the example above, the cup is pretty full—can you relate to it? We have a little space left at the top, and if you can stay within your stress cup without overflowing it, you can achieve a positive adaptation to your training.

Let’s assume my trainer says he has a great workout for me today: limit squats for four or five sets then full sprints afterwards. That might sound awesome, but the stress from the workout he planned for me might overflow my already full stress cup. Can my body successfully adapt to a training challenge that also over-filled my stress cup? No, I will experience allostatic overload. And, this failure to adapt will cause a huge stress response as the body and brain attempt to adapt. If this happens over and over, it will cause serious, deleterious health consequences far beyond an overtraining situation.

Allostatic Load and Daily Training

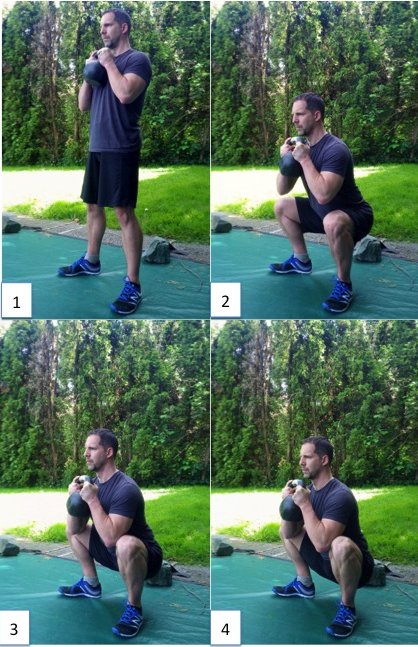

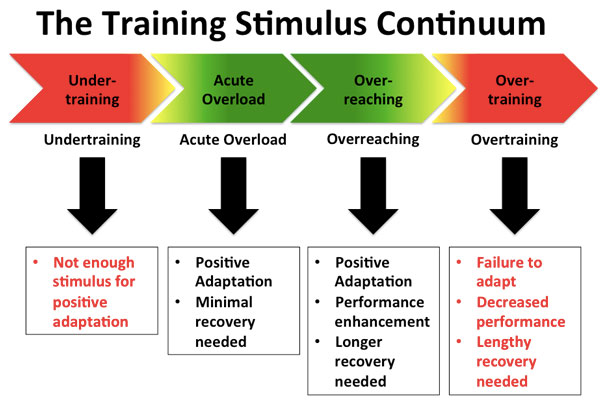

Undertraining is not enough stimulus for adaptation. The green area on the chart below indicates acute overload—a good workout session with good adaptation. Not much recovery will be needed. But, many times we will overreach with a session that pushes past our limits. While we can still experience good performance enhancement and positive adaptation, we must be cognizant of our recovery, which will take longer. Last, there’s overtraining, and since we can’t adapt to it we will have decreased performance and sometimes a very lengthy recovery period.

Too much overreaching without adequate recovery becomes overtraining syndrome, a medical condition. Overtraining syndrome is a prolonged imbalance of training load and recovery. For example, we might have a great session then rest for a day, then we hit it again and realize we need to rest more—but instead we do max deadlifts with no recovery. Basically, this will cause the stress cup to continually overflow since we have not allowed for recovery and have accumulated training load over time.

Overtraining syndrome is a big deal. If you truly have it, it can take months for a full recovery. While it happens more in elite athletes, it can happen with your clients, because they have other sources of stress beyond their training. Think about allostatic load and overtraining as the same thing. Your client might constantly have a high cortisol level because their stress response is over reactive. High cortisol for a long period of time is bad for body composition and general health.

A good coach should be able to spot the following problems early: fatigue, decreased performance, increased resting hart rate, insomnia, irritability. The stressed out brain starts overreacting. For example, if someone makes you mad at work instead of a calm conversation you snap at them—that’s the overstressed brain being more animal-like and it happens with overtraining too.

Remember, the brain is trying to protect you. So, if you feel like you shouldn’t be training, then listen and learn to spot this with your clients. Overtraining begins at this stage with a very animal-like dominant sympathetic system. Over time, if you don’t listen, your body can even become resistant to the fight or flight response. Parasympathetic overtraining means that you’ve dug such a deep hole for yourself that you can’t even raise your heart rate. I’ve heard of cases when people have needed one to two years to fully recover—and that’s not an exaggeration. It’s more than just your athletic performance, long-term failure to successfully adapt is the same as the long-term allostatic overload seen in all these conditions. In medicine, this is a new concept and new way of looking at chronic diseases.

Now, the mechanism—and this is in Strong Medicine as well—is that if your stress cup is overflowing for long periods of time, you are also generating inflammation or oxidative stress. Oxidative stress is an excess of free radicals or reactive oxygen species—and they drive chronic diseases. But if you’ve maintained your stress cup, even though you still get inflammation and oxidative stress from exercise, it will be short term and you will adapt to it. You need inflammation and oxidative stress to heal injuries, and for your immune system to respond to infections. Correctly dosed exercise can really be the fountain of youth.

Overtraining is catabolic. If your clients want to lose body fat and gain muscle, overtraining does the opposite. Excess cortisol wastes muscle and puts body fat in unfavorable places. The term “skinny fat” describes someone with low muscle mass, and low weight, but they look soft around the middle. Your clients don’t want that and you’ll need to educate a client who wants to try losing weight by eating an under 500 calorie a day diet while getting mashed under a high intensity exercise program. While they will lose weight with that plan, much of that weight will be muscle mass.

It’s important to keep in mind that we are all individuals with different issues filling the stress cup. Who are you training? It might sound intrusive, and your clients might wonder why you want to know about your stress, but it is important. You must know who are you training and what’s filling their stress cup. There are variations in what’s filling it, and there are many different sized stress cups.

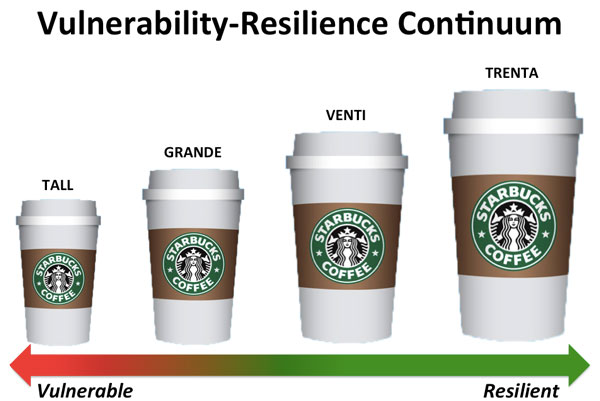

This chart is inspired by Starbucks. You can categorize your clients into a stress cup size. If they’re on the small side of the chart, they’re vulnerable, and you won’t be able to do a whole lot with them right now. Then on the other side, there’s a 20 year old who can go drinking all night ,and train hard the next day with no problems because their stress cup is huge. …But it will shrink if they keep doing that!

For example, let’s compare the 20 year old and a 40 year old stressed out executive. If I am a trainer who wants to do a cookie cutter (one size fits all) bootcamp workout, the 20 year old will have no problem with room to spare. But it will be too much for the 40 year old. Is your client vulnerable or resilient? It’s really important to figure out who you are training. Even if you have a smaller stress cup or are older, it doesn’t mean you can’t still perform at high levels. There are the Mike Gillettes, and Marty Gallaghers out there and many others in the room who perform at high levels—but they often need more recovery than when they were 20. But there’s some good news, through exercise you can slow that progression down significantly. Greater resilience is the picture of healthy aging. We can also reverse the process. Over time with smart training at the correct dosing, we can slowly build the size of the stress cup to an extent.

But the largest cup on the chart is not the norm. The small crumpled stress cup on the other side of the chart is the sad truth I face very often in public health. Many people of the general public are dying in their 60s and even earlier. These are the people we need to help. Sure it’s great to train an athlete who wants to enhance their performance, but you can really make a drastic impact on public health by training everyday people. Unfortunately, the medical profession is not doing it—they’re managing diseases, not preventing or reversing them.

Estimating the size of someone’s stress cup is not an exact science. If someone has high stress, a chronic disease, poor sleep, and very little exercise, we can assume he has a small stress cup (or “Tall” on the Starbucks chart). Another example might be a 45 year old female and the only reason she’s a medium (“Venti” on our chart) is that she’s 45. But otherwise she has minimal work stress, good sleep, no diseases, mediates regularly, and has a high fitness level. We intuitively know that we can’t train both of these clients the same way.

Hormesis

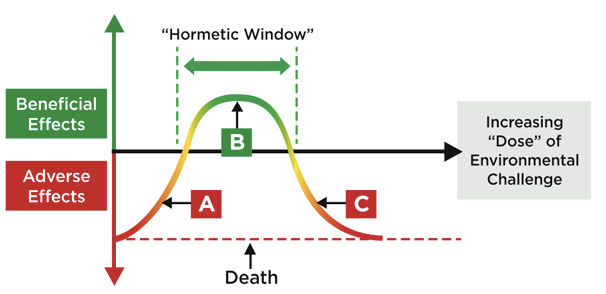

Before we discuss exercise and recovery doses, we take a little step back and talk about the concept of hormesis. I learned about hormesis from my toxicology training—a small dose of something might be beneficial, but the same thing at a higher dose could be harmful or cause death. Radiation is a perfect example. Lose dose radiation accelerates DNA repair—it helps our cells regenerate and repair themselves. But, high doses of radiation can kill us.

The famous quote is from Paracelsus in the 16th century. The chart below simply shows that when we go from left to right, the challenge increases. For our example, exercise, it isn’t really classic hormesis because doses that are too low are also bad. But there’s also a nice middle dose that’s “just right”, but as we continue to the right, the dose increases and begins to cause problems. In the example of exercise, point A represents a sedentary person who has very little physical activity. As we go right there’s an optimum dose that’s giving good effects, but if we keep going, overtraining occurs and can cause problems. The example can be made with food—under nutrition at point A, perfect the right amount of calories and the right kind of food at point B, and point C is over nutrition which we see all the time.

The hormetic dose is the ideal dose leading to beneficial change/positive adaptation. Much like pharmaceuticals, prescribing the correct exercise dose is crucial. Consistent under dosing leads to no progress—you need enough exercise to promote positive adaptations. And overdosing leads to overtraining. Exercise is more powerful than any pharmaceutical across the board. Pharmaceuticals just manage diseases, while you can reverse chronic disease and improve health with exercise. As a trainer, you should place as much importance on prescribing exercise, and think about it as seriously as a physician does with pharmaceuticals.

***

Chris Hardy, D.O., M.P.H., CSCS, is the author of Strong Medicine: How to Conquer Chronic Disease and Achieve Your Full Genetic Potential. He is a public-health physician, personal trainer, mountain biker, rock climber and guitarist. His passion is communicating science-based lifestyle information and recommendations in an easy-to-understand manner to empower the public in the fight against preventable chronic disease.