This is the third in a series of articles developed from Dr. Chris Hardy’s live presentation at Dragon Door’s Inaugural Health and Strength Conference. Click here to read the first article of the series.

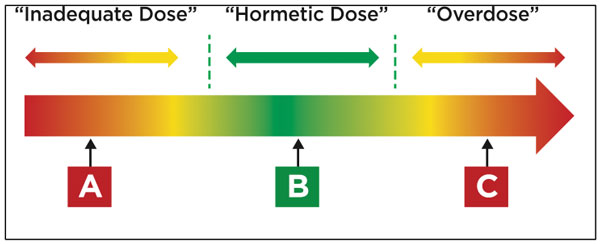

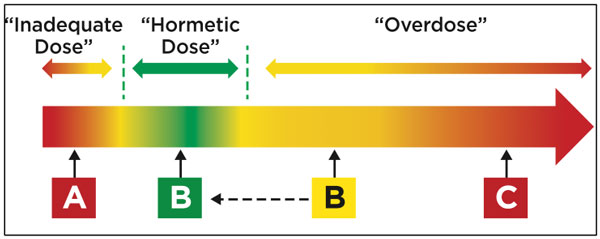

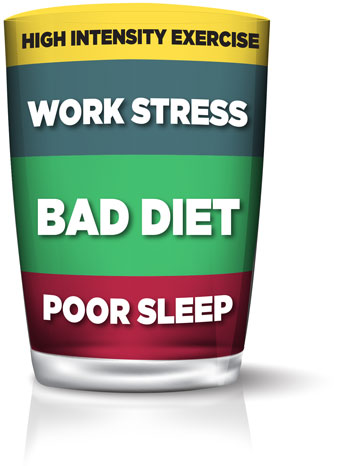

The Stress Cup dictates the beneficial, hormetic exercise dose. To apply this concept to our training, we need a scientific foundation—but it’s also an art. Elite coaches like Marty Gallagher—who has coached for over fifty years—have intuitively figured it out. In this article I will try to give you a foundation so that you won’t need all those years of trial and error to figure it out. Applying this science to your clients is the art of training. Since you already know how to adjust sets, reps, intensity, and volume, you’re already ahead of the game. We will try to hone your art with these concepts.

First, there are no hard and fast rules, this is more a conceptual thing. Remember that all of your clients are individuals and can’t all train the same way. Plus, their environments and stresses change from day to day. Our approach will allow for this day to day individualization.

Case Studies:

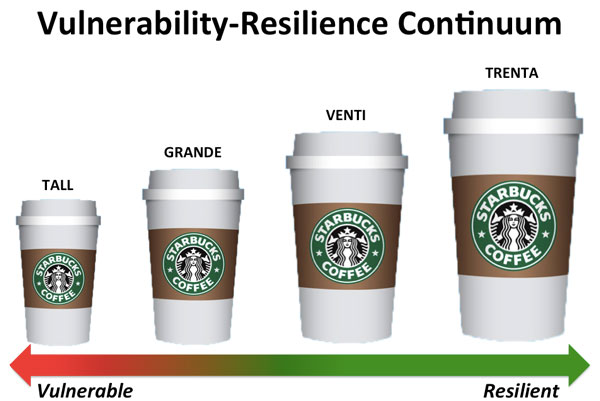

Our first example is someone with a “tall” stress cup. What’s filling his stress cup? On new client intakes, do you ask about their health problems? How about their stress levels and how they sleep? It’s really important that they tell you about these issues. This client has a small stress cup and a large amount of lifestyle stress will put him in allostatic overload. We will know that he’s been in this state for a long time if he has a disease resulting from a failure to adapt. Diabetes can be thought of as a failure to adapt to a lack of exercise, poor sleep, and/or terrible nutrition. The body will try to adapt to those stresses, and even though it does bad things for the body, diabetes is actually an adaptive condition.

So, how would we train this client? What would we do for strength training and for cardio? Like many other people, our client also doesn’t have a lot of spare time. One approach to consider for a guy like this is a stripped-down linear progression with a bit of a hypertrophy bias, in the 5-10 rep range. Diabetics and people with metabolic diseases work very well in that range and it helps clear out some muscle glycogen too. It’s beneficial, but it’s not the only way.

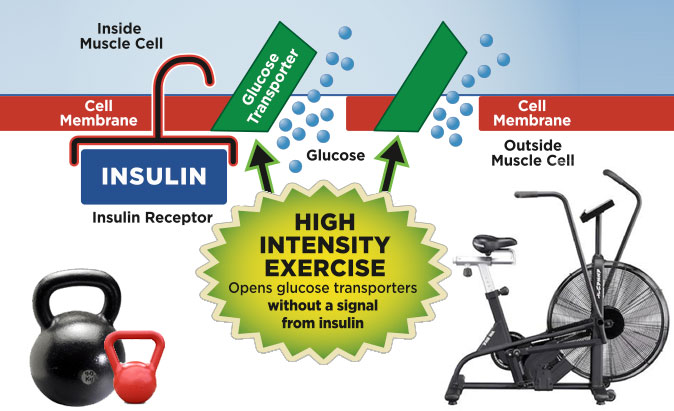

Let’s assume for example that he has diabetes and high blood pressure. Of course he could be walking but we could also try high intensity interval training—even low amounts of it can have incredible results for diabetics. Basically, it bypasses the normal insulin signaling mechanisms and gets some of the glucose from the blood stream back into the muscles. Emptying those glycogen tanks is really beneficial too, because lower glucose in the muscles will pull a lot more glucose from the blood. This process will increase insulin sensitivity for at least 24-36 hours.

But, while high intensity interval training is a really good approach for the diabetics, our example client also has a small, and nearly full stress cup. We need to figure out how much exercise is too much. With our example client it would be very easy to overdo it, so we need to remove the guesswork. We will use the Burst Cardio Protocol we describe in Strong Medicine. You don’t have to use it with all of your clients, but it is a fail-safe. When working with a client who is at risk of exercise overdose, but who could really benefit from high intensity training, the Burst Cardio Protocol is a very good choice.

This protocol uses heart rate to set both the interval duration and recovery times. Depending on the state of the client’s stress cup, they will respond to the same exercise differently from one day to the next. Heart rate response will be our window to the state of their stress cup. We will start with heart rate max, which is not the most scientifically accurate, but will be a close enough estimate for most of you clients. So, we’ll start by leading them to warm up, then we will start their interval exercises as hard as possible. The goal is for them to reach 95% of max heart rate, though 90% is the requirement. Once the client reaches the heart rate goal, they stop and recover until their heart rate is back down to 70%, then they begin another interval. This works well for a 20 minute session and can be done with kettlebell swings or snatches, or other modalities like the hand bike, elliptical machine, medicine ball slams or even burpees. You can choose anything anaerobic that will rapidly increate the client’s heart rate.

The key point of this whole protocol is that on the day when the stress cup’s load is low, there’s room for a higher exercise dose. Since a low stress cup equals parasympathetic dominance, this means the client will recover faster because the parasympathetic system will lower the elevated heart rate from the exercise. Faster recovery times will also allow the client to do more intervals during the set period of 20 minutes. If they are recovering more quickly, they’ll be able to start the next interval more quickly, too. When the stress cup is nearly full, there’s less room for exercise, and the sympathetic system is dominant. Recovery will be slower. If the client gets up to 95% and they have slept poorly, they will recovery more slowly since the parasympathetic system won’t be able to bring the heart rate down as quickly. The client will not be able to do as many intervals in the allotted time.

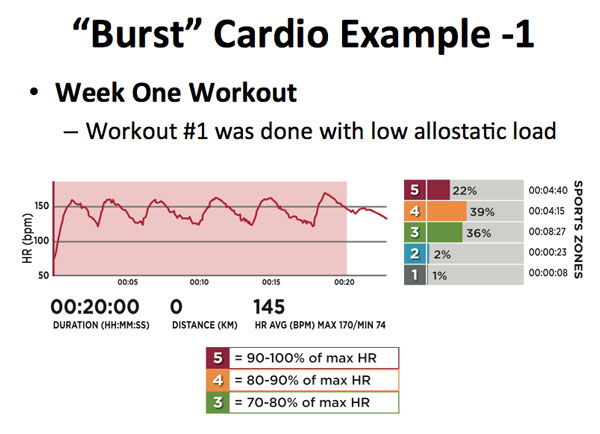

I’ve tested the protocol myself for a few years. One workout I tried a couple of years ago used the twenty minute time period. I did a hideous alternating combination of kettlebell snatches and medicine ball slams. It was rough. You can see on the chart below that I spiked up to 95% pretty quickly. I recovered and managed to get six intervals in 20 minutes—and that was on a day when I was feeling great.

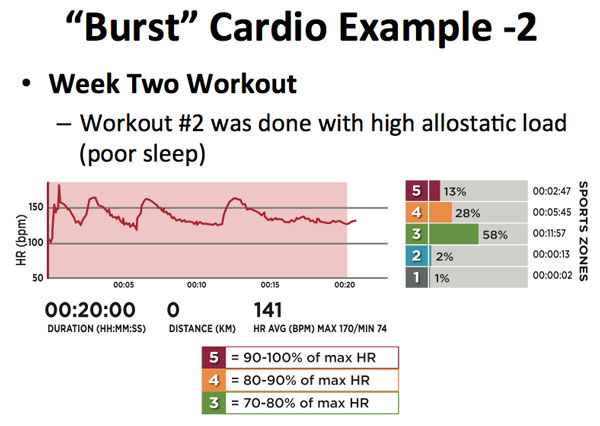

I waited a week later and tried the same workout when I had had a night of poor sleep. When I did the exact same workout with the same time period, look what happened on the chart below! I spiked up to 95% again, but then it kept taking me longer and longer to recover. After the 4th interval, it took me so long to recover that I never dropped below 70% before the 20 minute session was over.

So, even though I had fewer intervals, the protocol allowed me to exercise but not overdo it. My heart rate was a window into the state of my stress cup and adjusted the number of intervals for me.

The Burst Cardio Protocol automatically adjusts to the correct dose on a given day. As another example, let’s say that I’ve done a strength training session before my burst cardio. The strength training will affect the nervous system, along with my recovery time and the interval itself.

You can also use the Burst Cardio Protocol to train multiple clients with different stress cups. One client may end up doing more intervals during the time period, but since they will be regulating their own intensity you can concentrate more on watching and coaching their exercise techniques. When one client wants to know why they are not able to do as many intervals as someone else you can also explain how recovery itself is a trainable event. Between the intervals we can also coach our clients with breathing exercises and techniques to help them recover. A simple breathing technique such as breathing in, filling up the diaphragm, then slowly exhaling while watching their heart rate on a biofeedback device will allow a client to feel like they’re still training while they are resting. This technique will help them recover faster, too.

The protocol also works for mixed modalities—clients can do kettlebell swings for one round, the elliptical machine for the next, etc. I’ve tested it and found that when someone gets to 95% with kettlebell swings, it takes a lot longer to get back down to 70% as opposed to getting to 95% on the elliptical. The Burst Protocol also adjusts for the given modality. While it’s not necessary to use the Burst Protocol all the time, it is very useful if you are worried about overflowing someone’s stress cup.

The next post in this series will cover another common training scenario and how to use HRV and the Self-Rated Health Scale.

***

Chris Hardy, D.O., M.P.H., CSCS, is the author of Strong Medicine: How to Conquer Chronic Disease and Achieve Your Full Genetic Potential. He is a public-health physician, personal trainer, mountain biker, rock climber and guitarist. His passion is communicating science-based lifestyle information and recommendations in an easy-to-understand manner to empower the public in the fight against preventable chronic disease.

Dr. Hardy mentioned grip strength as a possible tool to measure the stress cup on a daily basis. There are studies that have shown that a decrease in grip strength is correlated with strokes, heart attacks and overall longevity—it made sense that it would also be an indicator of Central Nervous System health. I also liked the fact that it was a quick and easy check that I could do daily before I trained.

Dr. Hardy mentioned grip strength as a possible tool to measure the stress cup on a daily basis. There are studies that have shown that a decrease in grip strength is correlated with strokes, heart attacks and overall longevity—it made sense that it would also be an indicator of Central Nervous System health. I also liked the fact that it was a quick and easy check that I could do daily before I trained.